The Short Timers, a novel by Gustav Hasford, was the foundation for Stanley Kubrick’s war film Full Metal Jacket, but it was a close-knit group of Marines called the “Snuffies” that inspired all the characters. Earl Gerheim became Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (made famous by R. Lee Ermey) and Private Joker was based (at least in large part) on Hasford himself. There were others in the book (and the subsequent Full Metal Jacket cast) inspired by “Old Corps” Marines too, all men who served with Hasford at Phu Bai, the Battle of Hue, and other places in Vietnam — including well-known Hollywood technical advisor turned actor Dale Dye.

There’s a story behind the story, as you’ll see in the Chris Hernandez story below. DR

The Short Timers

The Snuffies and Full Metal Jacket

How the story about the story behind the story began.

It was April, height of the COVID crisis. I was cruising a Facebook photography forum, bored out of my skull, and saw a photo posted by Marine combat photographer Dennis Fisher. It was him in Vietnam with a camera and M3 Grease Gun, taken by a USMC combat correspondent named Earl Gerheim in Phu Bai after the Tet Offensive. As a former Marine, Army combat vet, photographer, military history fanatic, fan of the old Grease Gun and “writer, kinda,” I thought, “Wow, that’s cool.”

Combat Photographer Dennis Fisher with camera and M3 Grease Gun, taken by Combat Correspondent Earl Gerheim in Phu Bai after the Tet Offensive.

But something about that post burrowed into my subconscious, and later that day dug its way back out.

Gerheim…that’s an odd name. The only other place I’ve seen it was in a Vietnam novel called The Short-Timers by USMC vet Gustav Hasford. The main character was a Marine combat correspondent who winds up carrying a Grease Gun. And they’re in Phu Bai during Tet. And if I recall correctly, the guy named Gerheim was…

No way. It can’t be.

I jumped onto Facebook and reached out to Dennis Fisher. He confirmed that he did in fact serve with Hasford, as did Earl Gerheim. Fisher, Gerheim and I exchanged emails. Gerheim said Hasford used his name for two characters in the book, one of which was “Gunny Gerheim.”

You might know Gunny Gerheim.

The Short-Timers was published in 1979 but adapted for a movie that hit the big screen in 1987. In the movie, Gunny Gerheim’s name changed to Gunny Hartman. As in, Drill Instructor Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played by R. Lee Ermey, in a Stanley Kubrick flick called Full Metal Jacket. I had somehow stumbled into two of the Marines who helped inspire Gustav Hasford to write the book that became the movie that pushed thousands of ‘80s kids like me into the Marine Corps, and whose characters became icons of American culture.

Full Metal Jacket

Full Metal Jacket is a classic American war movie. Who doesn’t know The Gunny? Who hasn’t shared a meme of Animal Mother? Who doesn’t know that only steers and queers come from Texas? Who hasn’t made a War Face? Who hasn’t said “Me so horny” to their significant other? Who doesn’t know “The first and last words out of your filthy sewers will be sir”?

One of the more frequently used Animal Mother memes.

Actually, that last one tripped me up. I arrived at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego on a bus one dark night 31 years ago, exhausted from being up a full day and disoriented from riding aimlessly an hour from the airport to the fabled Yellow Footprints – which were, by the way, right next to the damn airport. I watched in terror as a DI approached, and a nervous voice exclaimed: “Here comes Smokey!” The DI walked up the bus steps, gave stern commands, and asked if we understood. We replied in crisp unison, trained by Full Metal Jacket, “Sir yes sir!” The DI, probably exasperated from hearing it a thousand times before, responded, “It’s just yes sir.” And we scrambled off the bus, a little dejected.

A few days after making first contact with Marine combat photographer Dennis Fisher we had a long and interesting phone conversation, and I saw photos he’d taken in country. The next day I spoke with combat correspondent “Crazy Earl” Gerheim, who was likewise fascinating and full of information. Then Gordon “Cowboy” Fowler, a Marine combat correspondent turned successful artist. Then Steve Berntson, a go-to Snuffie known in Vietnam for his ability to round up a quart of gin as well as new jungle fatigues. Then Bob “Ding” Bayer, Hasford’s closest friend. Then Dale “Daddy D.A.” Dye, that Dale Dye, another Marine from that small group.

“Crazy Earl” in Full Metal Jacket.

None bragged about themselves. All were eager to talk about Gustav Hasford, to ensure I understood his service, accomplishments, incredible intelligence, quick wit, and many, many eccentricities. Most of them loved the guy and generally called him Gus, sometimes pronounced “goose.” When I went other directions during interviews they’d often steer me back to Gus, which wasn’t exactly what I wanted. More on that later.

These men were the “Snuffies,” a small, tight-knit group of 1st Marine Division combat correspondents who served in “I Corps,” northern South Vietnam. They earned their pay by being pretty much a grunt with a notepad in line units (combat photographers like Dennis Fisher often went on missions with the Snuffies and remain close to some of them, but were in a separate unit). Their war was a curious anomaly, unique even in a conflict that had a thousand facets. There is no “standard” war experience; everything can change depending on where you are, what you do, and when you’re there. But the Snuffies experienced something far different than almost all other Marines, even those at the same places and same time.

“The Snuffies” celebrating Christmas, December 1967. Steve Berntson is front center, no shirt. Gordon Fowler is middle row with guitar, Dale Dye to his left, Gustav Hasford to Dye’s left. Earl Gerheim is seated at far right, beside the dark-green Marine.

The Snuffies were smart; plenty of other Vietnam GIs were smart, but the Snuffies needed above-average intelligence to get their MOS in the first place and several were college-educated. A couple including Hasford had already worked as writers or at newspapers, and four very bright Marines who’d washed out of officer training were sent to the Snuffies. They were well-read, followed world news, and “had conversations that would have been really unusual in line units,” according to Dale Dye, a prior mortarman. They also had to prove themselves useful so the grunts wouldn’t consider them dead weight. “When we’d get hit, it was important that the grunts in whatever unit I was with thought of me as Fowler and not ‘that idiot from division we have to babysit,’” Gordon Fowler said. “They had to trust me to fight beside them, not just write stories about them.” Simply put, you couldn’t find your own way around Vietnam, gain the trust of the infantry, and write good stories if you were stupid.

Then there was the Snuffies’ freedom. They carried printed orders from the division commander ordering anyone available to transport them around I Corps, and could pick and choose which units to embed with. “If we had a bad experience with, for example, India 3/5,” Steve Bernston said, “we’d say ‘Hey, Kilo 3/5 treated us better, let’s go with them instead’.” As crazy as this sounds to Global War on Terror (GWOT) vets, sometimes they even hitchhiked between outposts to reach their assigned units. “There was a standing order to always pick up a hitchhiking Marine,” Gordon Fowler said. That almost got Fowler killed once when he was picked up by ARVN (Army Republic of Vietnam) Soldiers who took him to what he thinks was a VC village, and he had to walk back to the main road to catch an American ride.

Lastly, every other Vietnam Marine had a gigantic, chain-of-command-shaped thumb on their backs; the Snuffies, on the other hand, were semi-volunteers on every mission. They received assignments to go with the infantry on various operations, which didn’t mean they had to be up front, but the Snuffies were constantly up front anyway. “We weren’t walking point or anything,” Bob Bayer said, “but there was pressure from the other Snuffies to get into it with the line units. We had a reputation to uphold.” So they jumped from line unit to line unit in ones and twos but never as a group, and kept getting into firefights, and kept getting wounded, just so they could do a good job telling the line Marines’ stories. Even draftee Gordon Fowler, 23 and married with a child when his lottery number came up, willingly risked it all.

“We were young, intelligent, creative guys who felt it was our duty to tell the story of the kid carrying a rifle and pack, scared to death out in the bush,” Dye said. “There were two ways to do that. You could hang out at the command post and interview grunts as they came back from the field, or get out in the field with them. We all wanted to be out there with them, and hated the idea that anyone would call us a pogue [POG, Person Other than Grunt] or REMF [Rear Echelon Mother Fucker]. We were out so much the grunts usually referred to us as JARs, Just Another Rifle.” Some grunts, upon learning the Snuffies hadn’t been ordered to accompany them on patrols and operations, expressed amazement: “You’re here, and you don’t have to be?”

Dale Dye with M1 Carbine, Vietnam, 1968.

Of course, being up front with the grunts meant constant brushes with death. There’s debate on this issue – Dye says the name came from hapless comic strip loser Snuffy Smith – but according to Steve Berntson those constant brushes with death are where the term “Snuffies” came from.

Steve Berntson, right, helps evacuate a wounded Marine in Hue not long before being seriously wounded himself.

When I read The Short-Timers I got the impression a Snuffy was a lower-enlisted Marine suffering the usual abuses the Corps inflicts on its young. Stupid me, when I was in I even used it once or twice, trying to sound “Old Corps.” But it actually came from the fact that E-5s and below went on all the missions while officers and senior NCOs generally stayed behind. If anyone was going to be “snuffed out,” it was buck sergeants and below. Thus the Snuffies were born.

Bob “Ding” Bayer was almost snuffed out by mortar shrapnel that barely missed his jugular. To the Snuffies, he just got “dinged.” Steve Berntson was hit the second time during Hue, after choosing not to go back to the rear, when a B-40 rocket and small arms fire tore him and several grunts up as they evacuated a wounded Marine. Earl Gerheim was wounded twice and Snuffy associate Dennis Fisher once. Dale Dye got two Purple Hearts; on one memorable occasion his flak jacket with Mad Magazine’s Alfred E. Neuman and What, Me Worry? drawn on the back was shredded by a grenade (if you watch Platoon, you’ll see the same drawing on Lt. Wolf’s flak jacket). Gordon Fowler, also awarded two Purple Hearts, joked “The guys figured anyone can be unlucky and get hit once, the second time was probably your fault, and after the third time you were bad luck and everyone avoided you.” Before Hue, Steve Berntson was on Operation Medina with a couple of Marine photographers. Shit hit the fan, Marines wound up in a brutal close-in fight, and photographer William Perkins posthumously earned the Medal of Honor by throwing himself on a grenade to protect the grunts.

Bob Bayer smiles while awaiting medevac with other casualties the morning after being dinged in the neck in the Que Son Valley, April 1967. KIAs were lined up a short distance away.

In a reunion photo of five Snuffies, Earl Gerheim points out that “Between the five of us are eleven Purple Hearts, three Bronze Star-Vs, two Navy Commendation Medals with Vs, a Navy Achievement Medal-V and a bunch of other medals you get just for being there.” Although never wounded, Hasford was awarded a Navy Achievement Medal with V for valor. To steal a line from the Vietnam movie Purple Hearts, being a Snuffy was no candy-ass assignment.

“Crazy Earl” Gerheim and Dale “Daddy D.A.” Dye await medevac after being wounded during Operation Ford.

The Snuffies had the usual contentious relationship with most of their leaders. Two of them, Master Sergeant George Wilson and Captain Mordecai “Mawk” Arnold, were beloved WWII and Korea vets who loved and protected their Snuffies. But Hasford made sure everyone who read The Short-Timers knew the Snuffies’ disdain for some leaders by having one officer do nothing but go to chow and rip his Marines off playing Monopoly for real money. In real life, one acting NCOIC gathered the Snuffies and proclaimed, “I’m taking the ‘combat’ out of ‘combat correspondent.’ From here on out, if anyone gets a Purple Heart they’ll be court-martialed for it.” The Snuffies looked at each other, said “Aye-aye, Gunny,” walked away and kept doing what they were doing.

Beloved Snuffy commander Major Mordecai “Mawk” Arnold, veteran of WWII and Korea, wearing his boot camp dress blues in 2017 at age 93. He passed away the following year.

Snuffy life had interesting perks, though. Snuffies escorted visiting civilian journalists like Eddie Adams, who took the infamous photo of ARVN General Loan executing a VC prisoner, and Catherine Leroy, the petite, foulmouthed French photographer who made a combat jump with the 173rd Airborne, was captured by NVA (North Vietnamese Army) during Tet, and convinced the communists to let her photograph them. Bob Bayer escorted a civilian photographer named Kent Potter on his first op in Vietnam, and had to practically hold the guy back from running into the fight. Potter died along with renowned photographer Larry Burrows when their helicopter crashed during the 1970 incursion into Laos.

French war correspondent Catherine Leroy preparing to jump.

The Snuffies also brushed elbows with notable Marine Corps leaders like 2/5 commander Lieutenant Colonel “Big Ernie” Cheatham, Captains George R. “Ron” Christmas and Myron Harrington, the commanders of Hotel 2/5 and Delta 1/5 in Hue, and 1st Lieutenant Fred Smith, CO of Kilo 3/5, south of Da Nang during Tet. Cheatham was a beloved leader who’d left an NFL career to serve in the Korean War and was awarded a Navy Cross for leading the fight in Hue. Christmas led one of the main pushes into Hue, was badly wounded and medevacked, likewise received a Navy Cross, and eventually retired as a Lieutenant General. Myron Harrington will forever be part of a Vietnam War mystery: the search for the famed and as-yet-unidentified “Shell Shocked Marine,” a frozen and mute Marine found by Harrington’s men and photographed by famed British photographer Sir Don McCullin. Steve Berntson may have been with Harrington when that frozen Marine was photographed, but unfortunately knows nothing about him.

National Galleries Scotland, “Shell-Shocked US Marine, The Battle of Hue, 1968, Don McCullin”

Fred Smith of Kilo 3/5, a leader known to do all he could to protect his men, was a Snuffy favorite. Dennis Fisher once took a photo of Smith calling in mortars and recorded himself on tape narrating the action. Decades later, Fisher was given Smith’s @FedEx.com email address. Fisher figured Smith wasn’t just a driver or clerk, and looked up the FedEx directory to find out Smith’s job. It wasn’t hard to find: “Fred Smith, Founder, Owner and CEO.”

Dennis Fisher with visiting USO girl Mary Grover after being wounded.

Life in the Snuffies meant getting a mission with a line unit, finding them on your own, going on patrols and major operations, getting shot at and maybe getting hit, coming back to the rear for a few days to file your stories, bullshitting with your buddies, getting smashed drunk at night, being assigned to another line unit on another mission, and heading back out. The Short-Timers author Gustav Hasford jumped headfirst into that life, and liked it. He wasn’t the most important Snuffy, but he was at Hue, where 142 of 2500 Marines committed to the fight died and almost 1100 were wounded. He bumped shoulders with Marine Corps legends and history and gave America a glimpse into the Snuffy world.

Gustav Hasford in Vietnam.

Gustav Hasford

I doubt many people are familiar with Hasford, so here’s a short-as-I-can-make-it summary:

Gustav Hasford grew up impoverished in Alabama. He edited a magazine and wrote articles here and there as a teen. Partly because Alabama’s schools sucked and partly from rebellion, Hasford dropped out of high school and signed up for two years in the Marine Corps. He became a combat correspondent but didn’t go to Vietnam until he requested to, with only ten months left in his enlistment. He wound up in the 1st Marine Division Information Services Office (ISO), what today we’d call the Public Affairs Office. Despite having immense natural talent as a writer Hasford spent two months as driver, coffee maker, errand boy and general flunky for lazy, no-talent lifers who’d wormed their way to an easy life in the ISO and wrongly thought Hasford’s hick accent meant he was stupid. Far from stupid, Hasford was a fun, smart, playful, odd guy; he was also, in modern parlance, an instigator. He enjoyed starting arguments just because, even about such arcane, non-Marine topics as classical French artists and Walt Whitman’s books. But during the Tet Offensive he was – finally – given an opportunity to escort a civilian journalist into Hue. Once there the journalist said “So long, thanks for the ride” and took off, leaving Hasford to his own devices.

Gustav Hasford (right) and Bill Cheeley admiring a centerfold. Fortunately, since pornography is banned for GWOT Soldiers not a single one of us ever looked at such filth while deployed.

As far as I can tell Hasford was in Hue just a few days, probably attached to provisional companies being thrown together as reinforcements. Then one day he decided to make his presence and judgment known at the worst possible time; as we’ll see, Gustav Hasford, questionable judgment and resulting chaos go together like the Eagle, Globe and Anchor.

Fellow Snuffy Steve Berntson told this story in 1993:

“I’d set up a base camp in Hue City, and Walter Cronkite rolls up with a camera crew. He was doing a stand-upper with some pogue colonel, asking about rumors that our guys had looted. Just then Gus busts in with two black onyx panthers and a stone Buddha on his back. ‘Hey, there’s a whole temple full of this shit,’ he hollers. ‘We can get beaucoup bucks for this stuff in Saigon!’ I hustled him outside quick, and Cronkite, of course, came back home and declared the war unwinnable on national TV.”

After this incident, when looters were being shot on sight, Berntson told Hasford to get his ass out of Hue and back to safety at Phu Bai.

Hasford had a hell of an experience in Hue but I can’t quite tell if he was in as much combat as other correspondents. Gordon Fowler, who rotated home just before Tet, met Hasford a couple months before that and initially wasn’t sure if he’d trust Hasford in combat at all. Bob Bayer said Hasford was in combat before and after Hue, and maybe during. Accounts differ on what exactly Hasford experienced, but after the war he wrote, “In Vietnam I fired more rounds than the Stonewall Brigade fired at the Battle of Gettysburg. I was highly motivated, but my body count was a standing joke: I killed as many of them as they did of me.”

Most of the Snuffies I interviewed fondly recalled Hasford’s goofy personality in Vietnam. Dale Dye, who took him on his first operation, was an exception. “I thought he was fucking nuts,” Dye said. “He had this sardonic, mean sense of humor. We all made fun of each other, but Gus made jokes that were really disrespectful. He and I argued a lot, especially when we were drinking. But after the war we were great friends.” GWOT vets, remember that one guy in your platoon who always got on your nerves and you occasionally wanted to choke the shit out of, but after deployment got along with great because he wasn’t in your grill all the time? That pretty much describes Dye’s feelings toward Hasford, and it’s not the least bit surprising. We know that you don’t have to always like your brothers, you just have to be willing to die for them.

Hasford, Dale Dye, and Bob Bayer on St. Patrick’s Day 1990.

A natural anti-authoritarian, Hasford joined Vietnam Veterans Against the War while still in Vietnam. After discharge he moved around constantly, worked a series of menial jobs, was briefly married and divorced, lived for a time in his car, asked fellow Snuffy Bob “Ding” Bayer if he could crash on his couch and didn’t leave for a year and a half, was employed by California’s largest distributor of sex fetish magazines, and collected literally thousands of books, all the while working on a novel he’d begun in Vietnam. As he wrote that novel, originally titled The Tattooed Chicken, he told Earl Gerheim which buddies he was putting in it.

Gerheim’s last name went to the DI and his nickname went to squad leader Crazy Earl. Rafter Man came from Eric Grimm, who really had that nickname and really did get drunk and hang from the rafters in the Da Nang E-Club but didn’t fall onto a general’s table like in the book. The platoon leader’s radioman Donlon was named after combat correspondent Tom Donlon, now passed away. Dave Martinez, a Hispanic kid from the Texas Rio Grande Valley, became Chili Vendor (I think). Bob Bayer’s personality became “Daytona Dave, an easygoing surf bum from Florida” and his name was used for Lt. Robert M. “Shortround” Bayer (Bayer has no idea where the nickname Shortround came from). Dale “Daddy D.A.” Dye inspired a character with the same nickname. Cowboy was Gordon Fowler from Austin, Texas, who had lived on a ranch, ridden horses and roped cattle. A corpsman buddy of the Snuffies became Doc Jay of the Lusthog Squad in the book and movie. Bits of Steve Berntson’s personality went into several characters. Hasford named Winslow Slavin, “honcho of the combat plumbers,” after Bayer’s high school buddy who they hung out with after the war; the buddy had never served in the military or anything, Hasford just liked him. Other names and nicknames of real Snuffies like Hamer, Babysan, and T.H.E. are sprinkled throughout the book. Bummer of all bummers, Animal Mother was not inspired by any specific Marine, though Fowler says “There were several guys just like that in the 5th Marine Regiment.”

Hasford’s habit of switching his friends’ nicknames and personalities among his characters made them wonder who was supposed to be who. When Steve Berntson asked Hasford why he’d done that, Hasford answered: “So you guys wouldn’t get mad and sue me for using you as characters without permission.” Some Snuffies had no idea they had a role in the book until they read it; Cowboy Gordon Fowler didn’t know, and his first question to Hasford after reading The Short-Timers was “Why’d you kill me?” In addition to being Cowboy, Fowler is convinced Joker is partly based on him.

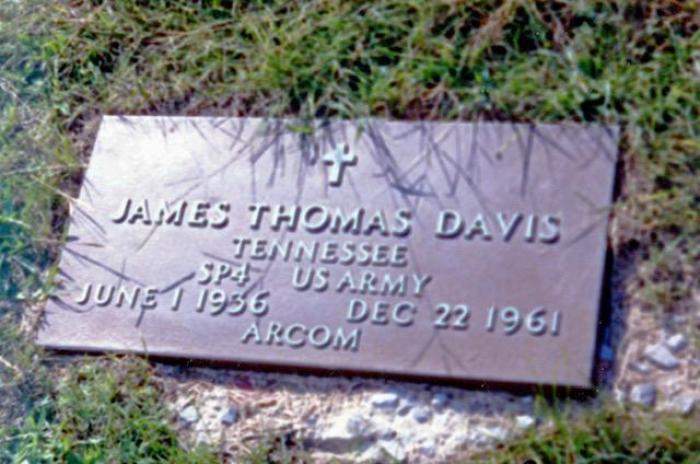

In an odd twist that Bob Bayer discovered after we first spoke, it turns out the actual name Hasford gave Joker – his own alter ego – was James T. Davis. There’s disagreement on this, but Davis is reportedly the first American Soldier killed in the Vietnam War. Hasford certainly thought he was the first KIA, as shown by his note on a photo of Davis’ grave. Writers are a morbid bunch; was this supposed to mean part of Hasford died in Vietnam, or something equally symbolic?

The Short-Timers received critical acclaim. Newsweek called it “The best work of fiction about the Vietnam War.” It’s a weird book, and was weirder in first draft; “It even had werewolves at one point,” Bob Bayer said, before he convinced Hasford to take them out. While often funny it is definitely not sunshine and rainbows, and ends with the polar opposite of a storybook happy ending. At its core The Short-Timers is dark, brutal, and utterly depressing, and as soon as I finished it one afternoon in 1988 I pretty much curled into a fetal ball of despair.

But that book was so hard-hitting I remember a lot of it verbatim, more than thirty years later. I only read it once, and don’t have a copy for reference. But I’m willing to bet five dollars that wherever in this article I quote the book from memory, I’ve got it mostly right.

While The Short-Timers is well written it is insanely over the top, and even as a clueless high schooler, I had to call shenanigans. On the other hand, much of what went into the book and movie really did happen, more or less. Hasford/Joker really did get chewed out for wearing a peace symbol button, but it was by an Army colonel on a big base rather than a Marine colonel on the battlefield. Cowboy Gordon Fowler really did bitch that “There isn’t a single horse in all of Vietnam.” The book’s mention of an overweight gunny blown high into the air by an anti-tank mine probably came from a Marine Hasford saw blown high into the air by a mine during Operation Pegasus. The mention of an NVA soldier who surrendered and gave information came from a real report by Steve Berntson. In the book and real life Snuffies put on Army rank and tried to sneak into an Army pogue chow hall, and got caught because combat Marines are capable of pretending to be lots of things but not pogue Soldiers. In the book, Joker describes the fight for Hue as “not a battle, but a series of overlapping riots”: that came from Crazy Earl Gerheim’s comment that “Hue is like 87 separate firefights happening at once.” I’ve never found any historical reference to it, and it was probably yet another Marine Corps urban legend, but Hasford told friends a recruit in another platoon shot a DI while he was in boot camp. Gordon Fowler said he never heard that story from anyone else, “but I wouldn’t be surprised if the Corps covered it up.”

I’m leery of any “they covered it up” claim without evidence. That said, one summer day when I was in boot camp, my platoon and another sat in bleachers for a class on the AT-4 anti-tank rocket launcher. We were hot and tired, struggling to stay awake, facing a wooden platform where an instructor talked a recruit through the firing sequence. The recruit held a training AT-4 with a built-in single-shot rifle whose round matched a real AT-4’s trajectory. Far to our right front, a cluster of DIs hung out waiting for the class to end. The instructor told the recruit to fire the weapon. I know the recruit was aiming at the DIs. He pushed the firing lever, and instead of a click heard a loud BANG! as the weapon, which had carelessly been left loaded, fired.

A round blasted out of the tube. DIs dove into the dirt as the tracer buzzed over their heads. The stunned recruit snapped his head back toward the instructor, mouth agape. We in the bleachers collectively gasped Oh, shit. The instructor stood wide-eyed and silent for just a second, then said, “The maximum effective range of the AT-4 is…” and droned on as if nothing had happened. He played off the near-disaster so well that I never heard a single recruit mention it, and I’m positive it was never reported. That would have been an investigation maybe resulting in charges and lost careers, and none of the DIs wanted that, so it just went away. So back in 1966 could a recruit have shot a sadistic Gunny Gerheim-style DI, whose fellow DIs knew an investigation would implicate them for allowing the abuse, and colluded on a cover story about a negligent discharge or something just to make the story go away? Maybe. Weirder things have happened.

Private Pyle with M1 in one of the most dramatic (and disturbing) scenes of Full Metal Jacket.

Whether the DI murder story was true or not The Short-Timers had a hell of an impact, and in the early ‘80s a man acting on behalf of Stanley Kubrick bought the movie rights. Kubrick then began his years-long quest to turn it into Full Metal Jacket, and hired Hasford as screenwriter along with Michael Herr, author of legendary Vietnam memoir Dispatches. In Hasford’s only meeting with Kubrick and Herr he acted like his usual self, which led Kubrick to pass a note to Herr saying “I can’t deal with this man.” But the three of them wrote the screenplay together, which turned Herr and Hasford into great friends, but then had a huge fight about whether Hasford should get full screenwriter credit, which pissed off Kubrick and turned Herr and Hasford into enemies. Hasford wound up being banned from the movie set in England but dressed in tiger stripe camo fatigues and showed up anyway, planning to hide among the extras. The screenplay fight lasted until after the movie was finished filming, at which point Hasford threatened to publicly accuse Kubrick of ripping off a Vietnam vet. Kubrick relented and Hasford got full credit as co-screenwriter, an amazing feat considering Kubrick was a moviemaking icon while Hasford was a nobody who never even signed a contract. His victory, such as it was, led to an Academy Award nomination for best screen adaptation. Hasford didn’t bother showing up to the ceremony, which was just as well, because he’d probably worn out his welcome in Hollywood.

As the Full Metal Jacket saga unfolded Hasford worked on book two of his intended trilogy, The Phantom Blooper (another happy story, about Joker defecting to the VC), and a detective novel called A Gypsy Good Time. He also started a feud by calling R. Lee Ermey a no-combat pogue, which I was surprised to find out is true; the Gunny was a great actor, rendered honorable service and will always be a Marine Corps celebrity, but according to never-wrong Wikipedia served in the Air Wing in Vietnam and had no Combat Action Ribbon.

Hasford had plans for many more books, and despite the Hollywood dustup and growing list of enemies his literary career was looking up. That career might have taken off, if Hasford hadn’t been plagued by his own bad choices. He fell in love with a woman who didn’t love him back, and just couldn’t let it go. He gained weight and started having health issues. As soon as he’d get a few bucks he’d run off to Paris, Australia or Africa and waste it. He lived in California and frequently visited his Snuffy friends in Washington State, which meant he’d often call for help from some truck stop or dusty small town where he’d been stranded by whatever hooptie he happened to be driving. Bob Bayer, in California, and Steve Berntson, in Washington, set a boundary; if Gus was stranded south of it he was Bob’s problem, north of it Steve’s problem.

While Gus came across as incredibly cynical in his writing, and maybe he was about the military, in real life he seemed hopelessly naïve. He bought an old cheap car from gypsies, after being warned not to, then had to abandon it when the sawdust leaked from the transmission. He let himself get screwed on royalties. He got wrapped up with some little male groupie who was clearly riding his coattails. But he was done in by, of all things, his love of books.

Hasford read constantly, was knowledgeable on multiple subjects, and if something came up in a discussion that he didn’t know he’d rush out, buy several books about it, and be an expert a few days later. Steve Berntson remembers seeing as many as three hundred books piled in the back seats of Hasford’s many jalopies. But several hundred of his collection of ten thousand books – literally ten thousand books – had been checked out from libraries and never returned, and he’d even used a fake name and SSN to get one library card so he could borrow, and keep, more books. Despite telling Bob Bayer “They’re not stolen, they’re just way overdue,” he was charged with felony theft. He might have beaten it, but even after police realized they’d badly overestimated the number of books he’d stolen– they’d mistaken books published by the University Press for books stolen from a university library – Hasford made the situation worse by being a smartass. He once walked out of court proclaiming in a Nixon voice “I’m not a crook” and commented that he was being persecuted by the “full power of the fascist state.” Instead of a slap on the wrist or community service he got six months in jail, and his attorney admitted to failing him. Hasford served three months before being released in mid-1989.

Snoopy with ball and chain that Hasford drew on a letter he sent to Dennis Fisher from jail.

“He was never the same after that,” Earl Gerheim said. “Prison really changed him.”

While in jail Hasford got depressed, stopped communicating with some of his close friends, and lost way too much weight. After getting out he developed (and ignored) diabetes, fantasized about requesting asylum in France, and transitioned from near teetotaler to aspiring alcoholic. He became obsessed with writing an expose’ on the college cop who busted him, convinced the guy was motivated by a personal grudge. When he got enough royalty money he fled to an island off the Greek coast, possibly because he thought the IRS was after him for back taxes.

His friends, who’d tried to talk him out of leaving, worried he’d never come back. But in 1993 he did come back – in a box, after his landlord found him alone in his room, dead from untreated diabetes and cirrhosis. At only 45 years old one of America’s most promising writers had been “pecked to death by chickenshits,” as journalist Grover Lewis wrote after his funeral.

But enough about Hasford for now. As I mentioned earlier, when I was interviewing his old comrades I often went in non-Hasford directions. I did that because Hasford, despite being the foundation of this story, isn’t the most important part of it.

More crucial than Hasford’s role are the actions, experiences and successes of the men who inspired him to write his book. Gus deserves all the credit in the world for cranking out the story and seeing it through to Hollywood success, but the men he served with were his raw material. When we ‘80s kids-turned-Marines look back on our movie Marine inspirations, we don’t picture Hasford the writer. We imagine badass combat Marines Cowboy, Crazy Earl, Joker, Shortround, Rafter Man, and Animal Mother. Which means we actually imagine Gus Hasford the Vietnam Marine, Earl Gerheim, Dennis Fisher, Eric Grimm, Dale Dye, Tom Donlon, Bob Bayer, Steve Berntson, Dave Martinez, Gordon Fowler, Snuffies we never heard of, and all those 5th Marine Regiment machine gunners.

The Short-Timers and Full Metal Jacket aren’t solely about Gustav Hasford. It was never just about Hasford.

Dennis Fisher, who served six months as a grunt before extending his tour to become a combat photographer, took some of the most amazing combat photos I’ve ever seen. He says most combat photographers didn’t have much combat training and unwittingly put themselves in danger, but “as an infantryman, I knew how to move around the battlefield and to keep my head and ass down while still doing my job.” He once helped a wounded Marine to safety during an ambush and assisted a corpsman in a vain attempt to save the man’s life. During another fight, he took a position with an M-60 team to lay down suppressing fire and was then wounded by mortars, “which fall out of the sky and are hard to hide from,” along with the entire gun team (the pictures he took of the machine gunner just before being hit are AWESOME). Earl Gerheim says, “Dennis just can’t take a bad picture.” Dennis had a long technical photography career after the Marine Corps, had a hand in filming Top Gun, Apollo 13 and Firebirds, and maybe someday we’ll forgive him for that last one. In 2012 he set up and operated the cameras for Felix Baumgartner’s parachute jump from the edge of space. These days Dennis is working through his old combat photos, identifying and tracking down the Marines in them to give them pictures of themselves in combat decades ago. Over fifty years after his tour, Dennis is still doing his job, telling his fellow Marines’ stories through his photos.

Dennis Fisher’s photo of Corporal Fred Angehrn, taken just before he and Fisher were hit by mortars.

“Crazy Earl” Gerheim didn’t sound crazy when I spoke to him, but in his youth he must have been an absolute madman. If you’re serving in a war and get the nickname “Crazy” it usually means the Joes you serve with respect the hell out of you, and you’ll probably be proud of that nickname forever. Gerheim is proud of it, although not in the way Hollywood might think. During conversation he displayed no brashness or fake tough-guy machismo. He doesn’t have to; he’s a twice-wounded Vietnam combat Marine, decorated for valor, who came home to a successful journalism career including several years in NYC as a sportswriter, and is now retired.

Gordon “Cowboy” Fowler is today an artist specializing in Texas landscapes whose work has been exhibited in several galleries. He’s married to a Grammy-nominated musician and still lives in Austin. While searching him online I found two little out-of-the-way references to him being the Cowboy of legend, but I doubt many Austinites know the Cowboy walks among them. I told Gordon I thought many people would be interested in art inspired by his memories of combat, and more importantly tried to convince him to paint my jacket in WW2 style with a pinup picture of my wife and Humvee on the back. It didn’t work, but I have high hopes.

Gordon Fowler and his wife, blues singer Marcia Ball (courtesy of AustinChronicle.com).

Steve Berntson arrived in Vietnam in April 1967 and was severely wounded ten months later during the Battle of Hue. He spent a year in the hospital before being medically retired, about a month before he would have picked up E-6, which he’s still pissed about. He had a great post-Snuffy life too, working thirty years on the Trident nuclear sub program. He took over as Snuffy reunion lead after Bob Bayer organized the first one, and everyone just assumed it was his responsibility from there on out, so he’s still doing it. Prior to Hue he spent six months covering 2/1, where he was christened “Storyteller.” He was there when a 2/1 company was ambushed, was told the point man was killed, and wrote a story saying so. Then at a 2/1 reunion a big Marine approached him and bellowed, “I’M NOT DEAD!” Taken aback, Berntson asked what the Marine was talking about. The man said, “I was on point the day you wrote that story about the point man getting killed, but it was someone else. You know how much shit I took for that? Everyone kept telling me, ‘You must be dead, the paper says so.’” Then the two old Marines had a laugh about it.

Steve Berntson on a trip to Vietnam in 2018. He’ll shake hands with any former NVA soldier but still hates the VC.

Bob “Ding” Bayer, AKA Daytona Dave AKA Mr. Shortround, extended six months in Vietnam, staying from January 67 until September 68, because “I felt comfortable there.” He was Hasford’s closest friend in Vietnam and back in the world, and retired after 24 years at the L.A. Times. He’s friendly, open, and loves to talk about war movies. He’s been back to Vietnam twice and will probably go again later this year. “I didn’t do any books or movies after the war,” Bayer says. “I’m happy just being a Snuffy.”

Bob “Ding” Bayer revisiting Vietnam.

Dale Dye, the most prominent of the Snuffies, served in Vietnam on and off from 1967 until 1970 and retired from the Corps as a captain. He’s had a successful Hollywood movie and TV career, advised for and acted in Starship Troopers (the best damn war movie ever) and other films including Platoon, Casualties of War, Outbreak, Saving Private Ryan and Band of Brothers, and even played President Mattis in Range 15. Because I’m a nice guy, I won’t mention his involvement in Firebirds. In Vietnam he and Hasford argued about which of them would be the first to write a book; Hasford was first and wrote three, another Snuffy named Michael Stokey wrote one, and Dye has written more than ten. He’s currently working on a movie about the 82nd Airborne’s defense of the La Fiere Bridge during the Normandy invasion.

Dale Dye in Starship Troopers. Would you like to know more?

Most Vietnam vets I’ve spoken to made no attempt to stay in contact with their comrades. I’ve talked to vets who haven’t seen or heard a word from a single man they served with. The Snuffies, on the other hand, are pretty tight; their first reunion was in 1978, and for a long time they had one every two years. A few have passed away, but most are in regular contact and some live minutes apart. As tight as they are, they’re also a bunch of type-A personalities who butt heads, disagree over politics or other nonsense, get on each other’s nerves, and need time away from each other. According to Steve Berntson, one Snuffy even bailed during Desert Shield, never heard from again, because he thought the others weren’t supporting his deployed son (if you happen to read this, sir, I think your brothers would love to hear from you).

None of this is a shock to modern-day vets; now that the internet allows us to hear everyone’s most lunatic thoughts all day every day, it’s a wonder every reunion doesn’t turn into Gangs of New York. But for all their grumpy old men tension, the Snuffies are still a real, no-joke brotherhood.

“A VA counselor asked me why I’ve been so successful and have my issues under control,” Steve Berntson said. “I told him it’s because any time I hit a low point, there were always five or six guys I could call at any time who were there with me and understood exactly how I felt.”

Bob Bayer, Earl Gerheim, Gustav Hasford, Gordon Fowler, and Steve Berntson at the 1988 Snuffies reunion.

After I first contacted Dennis Fisher and started researching Hasford I had a couple of shocking realizations. First, I hadn’t even known Hasford was dead; I’d figured that, like Forrest Gump author and Vietnam vet Winston Groom, Hasford had found one-time success before fading from the spotlight. Second, and even though the Snuffies will probably beat my ass for saying this, I don’t think I would have liked the guy. Sure, his bad attitude, intelligence, and shit-stirring personality would have made him fun to serve with in the Lance Corporal Mafia, but as a civilian, he seemed needlessly belligerent, vain, impulsive, flighty, unstable, and generally a frustrating pain in the ass. And it bugged me that he’d enlisted in the Corps, volunteered for Vietnam, and chosen to go into combat, but joined an anti-war group while an eager participant in the war he allegedly opposed.

He even addressed that hypocrisy in The Short-Timers: in one passage Joker/Hasford is spouting anti-war slogans like “War is good business, invest your son” and gets challenged by Animal Mother, who points out that Joker is also serving in the war by his own choice. Joker responds that he doesn’t really believe in the war and is “just playing a role in this farce.” Even as a kid I thought that was bullshit. Today, as a former Marine and retired Army National Guard combat vet of Iraq and Afghanistan, I see it as unbelievable bullshit.

Early in my Iraq deployment, I spoke with a staff sergeant from another Guard unit. I was on a convoy escort team, and to that point, we hadn’t been allowed on dangerous routes – all our missions had been boring milk runs. When I expressed frustration about going to war but being kept from danger, the staff sergeant gave me an old salt talk about how war sucks and why I shouldn’t want to be in it.

“I was in Desert Storm and the invasion of Iraq in the regular Army,” he said, “and trust me, war is terrible. You don’t want any part of it.” I wasn’t trying to be a dick but had to ask, “If it’s so terrible, why did you stay in after Desert Storm and come back for the invasion? Why did you join the Guard after getting out of the Regular Army and come back again? For someone who thinks war is so bad, you sure have volunteered for a lot of it.”

So yeah, I would have called shenanigans on Hasford’s “anti-war” stance. I probably wouldn’t have cared much for his lifestyle either. For all the fun and craziness of his time in the Corps and some of his postwar life, Gustav Hasford seems to have been a chaotic mess who just refused to grow up, and I wondered if he blamed his eternal adolescent turbulence on “what the war did to me.” Twenty-five-plus years of police work and nearly a decade of researching stolen valor and VA fraud has made me way too cynical, and I often throw the bullshit flag at the first hint, real or imagined, of vets using their service as a shield for bad choices.

But then I ran across a passage in an essay Hasford wrote after the release of Rambo, and I realized something: I was wrong to suspect there was any pity partying in Gustav’s head. Hasford, as far as I know, never blamed his quirks or choices on the Corps or Vietnam. I’m sure the war, and especially the intensity of the battle for Hue, influenced his personality; war leaves a mark on all of us. But Gus was who he was, war or not, and there’s a reason his fellow Snuffies so loved him and are fiercely protective of his memory. I think the reason is that he was authentic, honest enough to speak for them with words like this:

“Civilians, weaned on recreational gore, do not understand that unreconstructed Vietnam veterans are not misfits. We’re the first team, the varsity; we may not have been the brightest (the trouble with real life is that it’s all first draft), but we were the best. Maybe we didn’t have the money to buy our way out, but we had the balls to go to war, just as others had the balls to go to prison or Canada. What hurt us was coming home to confront civilians who were pale shadows of–and poor substitutes for–our loyal brothers in Vietnam. Civilians will never understand that if Vietnam veterans have been tortured, it was not by the Viet Cong but by the wives who still don’t know we were there, the parents who demanded that we not express our pain, the sisters who were afraid to let us hold their babies, and the girlfriends who believed that if they made us angry we would kill them, because that’s what the Vietnam veterans on television would do in the movies of the week that have been manufactured like cheese to accommodate the most irrational prejudices of a civilian audience.”

Hell yes, Gus. As a GWOT vet sick to friggin’ death of a public that assumes we’re all pitiful, damaged victims, damn do I agree. But that message was for our Vietnam forefathers, not for us Iraqistan vets. Without knowing it, Hasford did us younger guys a couple solids in another way.

Gustav Hasford at his desk.

Gus, being honest, gave us a cynical, ugly look at war, without visions of flags on Mount Suribachi or fantasies of fawning praise heaped on returning heroes. He showed us the US military at war isn’t so much discipline and order, but rather confusion, chaos, and frequent stupidity. He told us the causes would be flawed and the good guys even more flawed. He prepped us for the soul-crushing military ridiculosity we’d endure while fighting an enemy we didn’t understand for questionable reasons in a war we maybe didn’t even have to start. If we’d shown up in Iraq and Afghanistan with images of The Good War stamped on our subconscious instead of The Short-Timers, we might have died from shock. Gustav Hasford set the bar low for us, and anything better than what he told us to expect has been a bonus.

But another gift he gave us was even more important.

In The Short-Timers’ last scene, three Marines and a corpsman are down and wounded in a clearing, being shot repeatedly by an unseen sniper. They’re doomed, and any attempt to save them will only get more Marines killed. The Marines watching are bitter, salty, don’t-give-a-shit-anymore veterans like Animal Mother and “Lance Corporal Stutten, honcho of the third fire team,” who quit believing the Corps’ fables and propaganda long ago. Yet Joker watches, incredulous, as these bitter, disillusioned Marines line up and prepare to charge into the clearing. Even after he tries to talk them out of it, Stutten gives Joker a blank stare and gets in line, “ready to die for a tradition.” Whatever they felt about the war, they were still Marines who still had a job to do, and they weren’t going to abandon their brothers. Gustav Hasford may have been cynical as hell about the Marine Corps, “home of the phony tough and the crazy brave,” but he wanted us to know that Marines do their jobs no matter what. And when it comes to each other, we’ll die for our tradition. I know from firsthand experience that this goes for today’s Soldiers as well.

Maybe that’s the last word on the Snuffies, and why they’re so important. In the middle of a terrible, brutal, frustrating war, when they were likely to be wounded or killed on every operation and knew America supported them less and less, they still did their jobs, no matter what. They ran to the sound of the guns, even though nobody forced them to. They showed us, in reality and fiction, what bravery, dedication, and patriotism really look like, and in doing so became immortal-if-unheralded legends of the Old Corps. And I thank Gustav Hasford, the Joker in fiction and even bigger joker in real life, for telling the world about them.

Rest in peace, brother. And Semper Fi.

– Chris Hernandez

⚠️ Some hyperlinks in this article may contain affiliate links. If you use them to make a purchase, we will receive a small commission at no additional cost to you. It’s just one way to Back the Bang. #backthebang

I rank The Short Timers among the 10 best books I’ve read, and The Phantom Blooper among the 5. Reading the ST when I was twenty made me, just like the author of this excellent article, gung ho and wanting to become a soldier so salty that I would eat my own guts and ask for seconds. Having re-read the books over the years and now beeing a 43 yrs old father, I see Hasfords works in a completely different light. I feel endlesly grateful not having to experienced or taken part in the horrors of war. Full Metal Jacket is an OK war movie but it’s eons away from the anti war message that is expressed particuarly in The Phantom Blooper.

Well, duh. All this time I was wondering why people kept insisting Dale Dye had an M-14, now I finally realize they’re talking about the picture of Private Pyle about to shoot the DI. Yes that is an M-14. I didn’t add that picture to the essay, the editor did and I just missed the reference. My bad.

of all the accountings i have seen, read, watched & listened to about what combat is like, i believe i have (at least) a 51% grasp on what it is like, and a 100% hope that i never experience it. And with the current state of politics, i expect my 51% rating will increase to 100% sometime in the next 4 years? All the same, thank you Chris!

No “Sir, yes sir” in boot camp 1967? Hell yes there was ! Said and heard this sorry phrase a thousand times prior to my own deployment to Phu Bai then Hue City February 1968.

And who were we killing for?

God

Country

And the Marine Corps. ( in that order?)

Great article about a ruinous time in mine and other Marines lives !

Thank you!

Oh and good call on the M14 EBR in the ‘stan. Good to have some reach, huh?

Chris,

I’m NOT talking about the Carbine in Dale Dye’s hands; I’m talking about the RIFLE in Pvt Pyle’s hands just before he shoots Gunny Hartman. It’s an M14. Look at the front sight, bayonet lug, flash hider and exposed barrel between them and the gas cylinder. You’ll also note the the boots in the movie are carrying M14’s throughout.

Scout’s Honor, Brother: my primary MOS was 2111, aka Infantry Weapons Repairman. I’ve got a goodly bit of time on both the M1 and the M14

F’in autocorrect!!!

S’posed to be “Pvt Pyle”

Minor point; that’s an M14 in Oct Kyle’s hands, not an M1. M14’s were used in Boot Camp until very late 1973.

No way, sir! That is an M1 Carbine (or maybe M2, as someone told me). I carried an M14EBR in Afghanistan and own an M1 Carbine; check out the magazine, it’s way too small to be an M14 mag. 🙂

+1 agree with “boat guy” M14 in Pvt Pyle’s hands…

Wow. Thank you, Brother. Came over from your blog to read ” the rest of the story”. You have done our Brothers a great service by telling some of their story -and of telling us of them.

I first heard (read) the term ” Phantom Blooker” in Robert Roth’s “Sand in the Wind” the first novel I remember of that war. Recently I ran down a copy of Huggett’s “Body Count” to add to posterity’s library.

Chris, i could be wrong, but i don’t think Mr.Stokey has “a link to the article posted above”…my guess is – that’s the only copy that exists???

Fortunately it’s not the only copy. 🙂

https://medium.com/@WarriorsPublish/the-great-snuffie-trek-home-e7b8d39896ea

Thank you for this thorough article about my Dad’s beloved Snuffies. He was Major Mordecai “Mawk” Arnold, and thought of these guys as his sons. I recognize his handwriting in the upper right of the photo of the Snuffies, Christmas 1967. As long as he lived, he attended the Snuffies reunions, and in fact, I think he was the glue that held them together. Berny Bernston and Dale Dye attended the Celebration of Life we had for Dad, and Dale spoke, revealing many Vietnam stories we had never heard about Dad. Turns out he was quite a character along with his (respectfully said) crazy Snuffies. When Gus died, Dad and several of the Snuffies attended his funeral in Alabama. Gus had asked that his ashes be spread on a California beach “where the pretty girls would sit on him.” His mother entrusted my Dad with his ashes, and he brought them back to my house where he was living while he built a log cabin. Gus sat on our mantle for several months until Dad could arrange to fly to California to meet several other Snuffies to carry out Gus’s wishes. Thank you for honoring and giving some respect to these guys who certainly deserved it, but didn’t receive it when they returned from Vietnam.

Ma’am,

It was an honor and pleasure to meet these Marines and tell their story, and your father’s. Thanks for your comment, and for carrying your father’s memory. That’s important to many people, for many reasons.

Chris

P.S. I hear that “where the pretty girls would sit on him” wasn’t exactly what Gus said. 🙂

hmmm…making a short comment because I don’t see a “LIKE” button that i can click on???

Chris,

Just read your article. Brought back great memories. For an intro, I pulled three consecutive tours with ISO in Nam, Jan. ’67-Apr. ’69. In THE SHORT TIMERS I was Stoke the Supergrunt. Thought you might be interested in the Snuffies’ return to Nam, 50 years out.

MS

The great snuffie trek home

By Michael Stokey

Get some. I’m not sure what that some was anymore. A remnant of war, slip of the past, a time when everything was at its worse and you and the men around you were at their best – when you were really one for all and all for one? But, in our case, to get some meant you had to get there.

Enter Tim Davis and The Greatest Generations Foundation. Capt. Dale Dye, USMC Ret., a fellow First Marine Division Combat Correspondent had gotten to know Davis a few years ago. A trip most of us avoided for 50 years was in the brewing. A trip down the rabbit hole.

Some of the guys already prepared for an emotional ambush. We were U.S. Marine Corps Combat Correspondents and our Holy Grail was the press pass. It was the most bastard unit in Vietnam – in any war for that matter – and it was also one of the most casualty-ridden. One of our fellow loose cannons was Gustav Hasford, now deceased, author of the novel “The Short Timers,” which was turned into the movie FULL METAL JACKET. Other correspondents had slipped beyond the perimeter. Now, seven remained who agreed to make the run, nine Purple Hearts and three Bronze Star Medals for valor between them. Mostly sergeants at the time, they included Dale Dye, Mike Stokey, Steve Berntson, Robert Bayer, Eric Grimm, Richard Lavers and Frank Wiley. We signed the dotted line to go back again. To go back with each other. To go back alone? Sorry ‘bout that.

As TGGF had planned previous WWII veterans’ tours, ours was tailored to our particular battlefields. For Nam, it wasn’t so easy. There were few landmarks as in Europe. There were no markers pinpointing beachheads in the Pacific. Most of our fighting was in the jungles and rice paddies, places unrecoverable, impossible to retrace, impossible to find or plant your feet on again. There were exceptions, static outposts like Khe Sanh and, in our case, the infamous battle for Hue during the 1968 Tet Offensive. So, along with Danang and An Hoa, that was our itinerary.

Retracing their locations seemed accessible for Berntson and Dye. Their moments were smack dab inside the Citadel on the north side of Hue. They were already honed in, and with the help of our Vietnamese guide, Phan Van Vinh, they found the exact spots where they became casualties.

Hoping to vanquish some of the demons he carried, Berntson brought the shrapnel they dug out of him when he was wounded – a collection he brought for a donation. He found his spot, doggedly climbed the steep, uneven stairs onto a sloping hill. An odd site for a deposit – or so the raucous patrons of a close-by bar must have thought. They watched this American, obviously a veteran, struggle with his cane and emotions. And the dancing and din and music went soft. They knew why he got his wounds. By the time Berntson threw the twisted bits of metal into the dirt there wasn’t a breath.

Down the road, barely a block away, Dye recreated his own crucible. Leaning to fire around a corner, a sniper opened up on his flank. One round hit his rifle stock, sending a piece of plastic up through his chin, pinning his tongue to the roof of his mouth. One of his more fortunate wounds. Bullet holes were still in the wall above his head.

I may have been the only one who didn’t anticipate a trigger. My face-downs with terror came in the bush. Except for smells, what was there to find? In Hue I escaped unscathed, physically and psychically, and had no ghosts in waiting. But the funny thing is, I think mine came first, on our second day in Danang.

We were taken to a tiny bar called Tam’s in the midst of the teeming ramshackle jungle of Danang. I don’t know why it hit me so hard. Like the time I was struck by the first round fired before there was the urgency to duck. It smacked me like a shockwave.

Like the others, I entered the shack which advertised food and beer and scooters and surfboards. I didn’t notice any surfboards or scooters because I was drawn into the shack like a tunnel. Gilding the walls were hundreds of photos of the war and soldiers who fought for the south. It was like a blast furnace sucking me into the heat. Photos everywhere, on the walls, the furniture, the shelves. Snapshots of Marines in villages, soldiers on the hump, soldiers holding babies. There was old, rotted military fatigues and gear, canteen cups and jungle boots. They still had a smell to them. Grunts know it; a mixture of dirt and chlorophyll, sweat and blood. A dank, sick sweetness. There were old dog tags. I picked one up to take a look when Tam, the owner, pulled me down to talk.

She spoke in good English. She was 65, yet to those of us who still seemed spry, she seemed the perfect caricature of an elderly mama-san. Hell, we were older than her. She spoke fast, her words a rush, incredibly grateful to host veterans in her pub. And she talked.

As a young teen, the Viet Cong gave her a booby-trapped Coke can and told her to walk it to the 1st Marine Division security gate. Rounding the hill and out of sight, she struggled with pidgin English to tell the guards it was a bomb. She pleaded with them to safely explode it nearby. The explosion was important – proof to the VC she delivered the device. There were other tests, but in time the Americans left and the communist armies swept south. Declining to join the exodus of boat people, she was ushered to one of the notorious reeducation camps.

After her release, she eventually opened her pub. As more photos went up, more pressure by the state was applied. Through the years she had been closed down, maligned by the press, jailed for treason and unremittingly threatened. Even today it wasn’t completely safe. But things were looking up and opening up.

I listened and looked around again. Then I saw another photo. . .of a buddy I wasn’t able to save. It wasn’t him, but it looked like him, enough to send me plummeting.

I needed air and it all flooded back, the staggering memories, the hurt and despair, overwhelmed again by the carefully buried loss and futility. It was a 30-second shutdown, another 30 to stop the tears and shakes. My brothers stood guard. . .but left me alone. In a flat minute I was collected again because there’s no point being stuck on a battlefield. And through it all Vietnam seemed just fine.

That was the hardest to reconcile. It wasn’t just us. Tam was stuck, too. Stuck in her courageous shrine.

Socialist slogans and billboards abounded. Propaganda was sublime. The museums would impress Lewis Carroll. While I found great humor in it, Dale Dye did not, refusing even to enter the museum at Khe Sanh. As I opined to a Dutch tourist who was visiting the plateau, “I knew we lost the war. But I didn’t know until now that we lost every battle.” But the North Vietnamese weren’t the only ones who penned the history of the war.

Flags flourished everywhere you looked or drove, outside every house, hotel and hamlet. Typically, a secondary flag with a gold hammer and sickle flew adjacent. You don’t know if they are planted by the government or are displayed by the people lest the bureaucrats suspect their allegiance. When the Montagnards have flags flapping outside their huts you know Big Brother is watching.

City life is noisy and vibrant. As Dye so eloquently alluded to in his final post, it may call itself the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, but the thriving underbelly of capitalism is alive and kicking. And that was tough to resolve. Lest you think this evolution is automatic, I posit a little shop of horrors called North Korea.

You still see scores of caged chickens and piglets on the backs of motor scooters but now the drivers are texting. The burgeoning population of dogs are well-groomed and there’s scarcely a sight of beetle nut. The girls wear masks (for pollution) and fewer ao dais. Ramshackle huts fill the urban sprawl but so do luxurious hotels. Our interpreter, Vinh, tells us even the water bo are friendly. Most impressive of all, a massive fire-breathing Dragon Bridge spans the River Han in Danang. Welcome to the new Nam, Skippy.

As of our arrival, Vietnamese likeability of Americans hovered at 87%, compared with a 17% favorability for the Russians and Chinese. If America shunned her surviving troops, the South Vietnamese seemed to acknowledge them. Worth it? It has to be. Along with the wall, it’s all we got. But it would not be so if Oliver Stone’s portrayal of our troops was all we left in our wake.

Finally, we begin to pack our gear. This just in: Students and teachers riot, burn the American flag at Berkeley. No, the headline isn’t from the Chronicle’s morgue in the ‘60’s. The news is current.

Ten heady days and we were back on the Freedom bird, heading back to the Land of the Big PX. Ten days of grace and glee and ghosts with our brothers. And gratitude. It was Tim Davis and The Greatest Generations Foundation staff, Brandon Cope, John Riedy, Embry Rucker, Adam Weissman, Jason Inglis, Jeffrey Nuttall, and two fellow veterans, James Hackett and William Reynolds, who generously and gratefully took us back inside the wire.

-30-

Mr. Stokey,

Thank you for your comment, and I think I remember your character in the book. If I recall correctly, Stoke was killed by his own grenade, correct? Dale Dye told me your nickname was “The ARVN” because you had been in Vietnam so long. I apologize for not reaching out to you for this article, but it was already so long I had to stop after interviewing the other six. I’ll email you shortly.

Do you have a link to the article you posted above?

You clearly dont know jack about firearms or haven’t seen the film…its an m14.

Outstanding