What Cops Ought Need to Know About Autism

Chris Hernandez

As I’ve written before, I have an autistic son. I’ve also been a cop for almost 23 years. So when I saw the video of North Miami PD shooting the caretaker of an autistic man last July, and heard the officer’s explanation that he was actually trying to shoot the autistic man, I was…perplexed.

Just from a tactical perspective, I didn’t get the reasoning behind that shooting. From the camera’s angle I didn’t see anything that looked like a gun, I clearly saw the caretaker with his hands up explaining the situation, and I didn’t get why the caretaker was cuffed after being shot if the officer supposedly fired to protect him.

But most importantly, I saw the autistic man doing something that could have been a sign to the responding officers.

On many occasions I’ve seen my autistic son lift objects to his eyes like that, or rub his fingers together at the corners of his eyes. Had I been on that scene, I would have immediately told everyone to back off, and explained why. The officers on that scene, through no fault of their own, seem not to have recognized that sign.

I’ve never been scared of a cop (at least in America; overseas was a different story). Despite the alleged oppression Hispanics have suffered, despite having family members complain to me about their awful treatment when they were arrested for things they were actually guilty of, despite the usual negative portrayal of cops on TV and in the media, I was never, ever, scared of an American cop. But now that I have an autistic son, I have to worry. Because I don’t know if my son, when he reaches adulthood, might somehow wind up in a situation where an untrained police officer might mistake him for a threat.

When I became a cop in 1994, I don’t remember any training about autism. We get some now, but what I’ve received is more about the basics of autism than how it specifically applies to my job. The number of kids diagnosed with autism has skyrocketed since I started this career, so new cops can expect to encounter a lot more autistic people than I ever did.

I speak autism and I speak cop, so after the North Miami shooting I started trying to figure out ways to spread knowledge about autism to street cops. I’ve come up with some examples, based on firsthand knowledge, of situations where a cop might mistake an autistic person for a threat.

First, I should say THIS IS ORIENTED TOWARD PATROL OFFICERS. Pretty much every other type of cop (detectives, accident investigators, etc.) arrives after the situation is settled and main players identified, but patrol shows up to mass confusion and a thousand unknowns. Patrolmen need this more than any other type of cop.

EXAMPLE 1: You’re on patrol and get a “see complainant” call at a house, with no additional information. You arrive at the house, knock on the door, and get invited inside. Inside the front room are a middle-aged couple and a teenage boy. Everything is calm. As you begin talking to the middle-aged couple, the teenage boy suddenly grabs your arm and yanks you toward the front door.

What would you do?

Something similar happened to me while I was conducting an investigation. I knew when I entered this house that a teenage boy with autism lived there. When he grabbed my arm and pulled me toward the door, I knew exactly what he was doing: he wanted to go for a ride. He wanted me to put him in my car and drive somewhere. I knew this because my autistic boy loves to go for rides, and has done the exact same thing with me many times.

As cops, we should always be vigilant. We should always be prepared to encounter a surprise threat. If I hadn’t known an autistic person was in that house, and didn’t have an autistic son myself, I would have reacted defensively when that teenage boy grabbed me. I would have yanked my arm away. I would probably have shoved him away to create distance. I would likely have drawn a Taser or baton. And none of that would have been necessary, because the boy wasn’t any kind of a threat.

If I had reacted like a cop instead of the father of an autistic son, I would likely have made the situation worse. Foreknowledge of autism kept me from overreacting and maybe harming an innocent person.

Example 2: You receive a “prowler” call in a neighborhood late at night, with a detailed suspect description. You drive into the neighborhood, turn a corner and see your suspect walking down the street. You drive up to him, get out of your car and yell at him to stop. He immediately sticks his fingers in his ears.

Most cops I know would get mad. We’ve known since childhood that sticking your fingers in your ears means “Lalalalala I’m not listening to you!”, and that would piss most of us off.

But you know what else it could be? It could be an autistic person who wandered from his house (like the man in North Miami) and has sensitivity to loud noises. I’ve been around autistic kids who have to always wear hearing protection because they’re so sensitive. I’ve seen my son melt down at an airshow, even with earmuffs, because he couldn’t stand the sound of the Blue Angels flying overhead. I once took him with me when I taught a class on autism, and at the end when the audience applauded he immediately stuck his fingers in his ears.

[Photo from FriendshipCircle.Org]

Example 3: You make a “routine” traffic stop on an SUV. A driver and passenger are in the front seat. As you’re getting out of your car, you see the passenger take his seat belt off, climb over his seat and disappear into the cargo area. Threatening or not?

One night a long time ago I found a vehicle that had just been involved in an aggravated robbery. The passenger was reportedly armed. When I turned around behind the vehicle, the passenger looked back, reached down and dropped the seatback so I couldn’t see him. Was he drawing the pistol he had just used in the robbery? Was he prepping an AK? I had no idea.

Yes, the passenger in example 3 could be a threat. I’m not telling anyone to disregard that possibility. But it could also be someone like my son: very often, as soon as we stop the car he pops his seat belt and climbs into the back of our SUV. People with autism often do things that make no outward sense, and in the wrong situation we cops can badly misinterpret those things.

Example 4: You get a call of a man either naked or in his underwear walking around an apartment complex parking lot speaking incoherently.

If your patrol areas are anything like the beats I worked, your first thought was probably “PCP.” People on PCP often take all their clothes off because their skin feels itchy or crawly or something, and they ramble nonsensically. They can also be insanely violent. Getting a call of someone outdoors in underwear acting suspiciously was reason for me to prep for a fight.

But my son also likes to run around naked, or in his underwear. And he rambles, repeats phrases from songs or random conversations, or says things that make no sense. If my son was an adult, got out of the house at night and did those things, a reasonable person would call the police on him. When the officer arrived, my son wouldn’t respond to his commands. And a reasonable cop would think my son was on PCP or something similar.

But he’s not. He’s just a little boy, with a problem that looks like something else.

Autistic people can display a lot of odd behaviors. Talking to themselves, spinning, suddenly sprinting away, tapping on things repeatedly (like hundreds of times a day), rocking, humming, chewing strange objects, wearing clothes backwards, spitting, all kinds of things. They can be aggressive. They can also overreact to things that don’t bother typical people and ignore things the rest of us would freak about; for example, my son screams like he’s being tortured when we cut his toenails, but barely cried when he broke his arm. Their actions can mimic dangerous, drug-induced behaviors. So we cops need to not jump to conclusions when we see someone acting in ways that look criminal.

The problem is, autism isn’t always so easy to recognize. You’ve probably seen videos posted online of kids melting down in public as parents try fruitlessly to calm them; those videos are usually accompanied by comments like “This is what’s wrong with parenting today” or “That kid needs a spanking.” Those commenters don’t see what I see: a kid who’s probably autistic and whose parents don’t want to resort to physical force.

In my first year as a cop, I was on an accident scene. I saw two men standing on the curb and asked if they were witnesses. One said he saw the accident; he was extremely nervous, but that’s not so unusual. But when I started talking to him, the other man began waving frantically and mouthing something I couldn’t understand. I told him to wait, and went on with the interview.

The witness haltingly told me what he had seen. Then he said, “Officer, I need to show you something.” He took out his wallet, pulled a small badge sticker out, and asked, “They gave me this at school. Does it mean I’m a police officer?”

Until that moment, I had no idea the man had a disability. The other man had been trying to tell me about it, but I didn’t catch either his warning or the subtle signs of the witness’s problem. Some autistic people are so severely affected you recognize it right off the bat, but those aren’t the ones you need to worry about. The concern is with those you don’t recognize as autistic.

Guys, please keep in mind: NOTHING I SAY CONTRADICTS ANY OFFICER SAFETY TRAINING. I am NOT telling officers to put themselves in more danger. I’m saying some autistic people may not immediately be recognizable as autistic, some autistic behaviors may look more threatening than they actually are, and in some situations an officer may be able to re-assess what they’re looking at, ask if they’re dealing with an autistic person rather than an uncooperative or dangerous suspect, and say, “This might not be what it looks like.”

One crappy truth is that some autistic people can be dangerous. Not because of the autism, but because of other problems such as schizophrenia, psychosis or violent ideations. According to a CNN report, “Research has shown that people with autism spectrum disorder are no more likely to be violent than the rest of the population. A 2008 review found that 84% of violent offenders with autism also had an underlying psychiatric disorder at the time they committed the crime.” The Sandy Hook shooter was on the autism spectrum, but had other issues that led to the mass murder. The Fairchild Air Force Base active shooter in 1994 was diagnosed by one psychiatrist with Asperger’s (that diagnosis is suspect), but had multiple other psychological problems. A high school student with Asperger’s plus violent ideations was caught as he planned a mass school shooting and bombing in 2013.

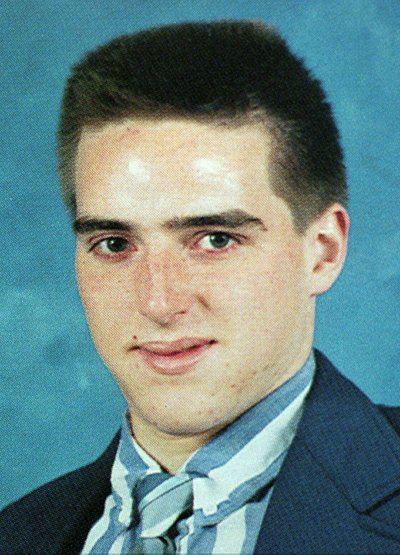

[Dean Mellberg, the Fairchild Air Force Base active shooter]

But the vast majority of autistic people aren’t dangerous. And if we encounter an autistic person like the one in North Miami, who was reported to be dangerous and was acting in a way that looked aggressive but wasn’t, we don’t want to mistake this innocent person for a lethal threat. Guys, too much of the public hates us already. We don’t need to start killing autistic people and make it worse.

Last thing, and it really sucks to admit this: As a street cop, I wasn’t cruel, I wasn’t brutal, but I was hard-hearted. I worked rough areas and dealt with murderers, rapists, robbers, about a million crack addicts, and all the nonsense that follows them. I viewed everyone with if not suspicion, at least cynicism.

And I know, without question, that I dealt with people on the autism spectrum. But I didn’t recognize it back then. I didn’t realize I was dealing with people who needed help, and I didn’t treat them very well. And now I have to worry that my son will run across a cop like me someday.

My little autistic boy.

I can’t fix anything in the past. But by talking to cops about autism, I might protect my son from future bad encounters with police. I know: that’s a totally selfish goal. But maybe, if I get the word out to enough cops and their departments, I can help other autistic sons and daughters too. And maybe I can even prevent some young cop from ruining his life by killing an autistic person he thought was a threat.

–C.H.

Breach-Bang & CLEAR!

Comms Plan

Primary: Subscribe to our newsletter here or get the RSS feed.

Alternate: Join us on Facebook here or check us out on Instagram here.

Contingency: Exercise your inner perv with us on Tumblr here, follow us on Twitter here or connect on Google + here.

Emergency: Activate firefly, deploy green (or brown) star cluster, get your wank sock out of your ruck and stand by ’til we come get you.

Chris Hernandez (Mad Duo Chris, AKA “Autism Dad”), seen here on patrol in Afghanistan, may just be the crustiest member of the eeeee-LITE writin’ team here at Breach-Bang-Clear. He is a veteran of both the Marine Corps and the Army National Guard who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also a veteran police officer of two decades who spent a long (and eye-opening) deployment as part of a UN police mission in Kosovo. He is the author of White Flags & Dropped Rifles – the Real Truth About Working With the French Army and The Military Within the Military as well as the modern military fiction novels Line in the Valley, Proof of Our Resolve and Safe From the War. When he isn’t groaning about a change in the weather and snacking on Osteo Bi-Flex he writes on his own blog. You can find his author page here on Tactical 16.

Chris Hernandez (Mad Duo Chris, AKA “Autism Dad”), seen here on patrol in Afghanistan, may just be the crustiest member of the eeeee-LITE writin’ team here at Breach-Bang-Clear. He is a veteran of both the Marine Corps and the Army National Guard who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also a veteran police officer of two decades who spent a long (and eye-opening) deployment as part of a UN police mission in Kosovo. He is the author of White Flags & Dropped Rifles – the Real Truth About Working With the French Army and The Military Within the Military as well as the modern military fiction novels Line in the Valley, Proof of Our Resolve and Safe From the War. When he isn’t groaning about a change in the weather and snacking on Osteo Bi-Flex he writes on his own blog. You can find his author page here on Tactical 16.

Like the perspective in this article. However, may I respectfully point out that the film of a child having a meltdown in a mall is – presumably – posted without consent (of the disabled child involved). I will explain why this is problematic.

A meltdown is a complete loss of control due to sensory and/or emotional overload and filming this type of event is, in many autistic people’s opinion, voyeuristic and intrusive. It is certainly not helpful to do so. Would you find it acceptable to film someone having an epileptic fit and post it in this way? What about someone with a condition like dementia? Is it OK to film and share footage of that? What if it were you in this position? How would you feel if it happened to you and you discovered later that someone had filmed your intense distress in this way and posted it on YouTube?

I understand the intent was to inform, however, please bear in mind that you are sharing someone’s personal difficulties and, if they are autistic and therefore disabled, they have no way of consenting adequately to what you are doing.

Thank you again for the rest of the post, I found it interesting and informative.

Generally speaking, events recorded in public view aren’t subject to privacy restrictions. We recently posted video of someone being murdered; that was definitely posted without the victim’s consent, but served a much larger and very important purpose. That video, like this one, could potentially save an innocent person’s life.

Thank you for your comment and observation.

Thank you for your response. I know that privacy restrictions don’t apply here, it was really more of an ethical question I wanted to raise. Maybe it’s cultural (I’m posting from the UK, and have lived elsewhere in Europe where attitudes towards privacy and children are maybe different to those on the other side of the Atlantic), but it makes me feel very uneasy seeing footage of a child posted in this way.

All kids are vulnerable, and we live in an age when parents are advised not to publicly post images of their children online…you’re a cop, I don’t need to explain why that is. A child with a disability is doubly vulnerable, and in this film, the kid is easily identifiable. I don’t know if he is your son, in which case I guess you can make your own choices about protecting him, but if that were my autistic child, that film would makes me feel a little afraid. As it is, I just feel really uncomfortable.

Again, my intent is not to criticise, and I very much appreciate your post which gives a lot of valuable insight into how an uninformed police officer might perceive autistic behaviour.

Great article, and great advice.

I had a situation where I was in the parking lot of a condo complex, talking to both drivers out a crash. Safe area, everybody cooperative, had my back turned to my cruiser. One of the drivers starts looking over my shoulder, and I look back to see a guy (over 6 foot, and large) climbing in the driver’s seat of my cruiser. I start giving commands, but he’s telling me he’s just going to drive my car back to the station… order him out, and he gets out…it came really close to being a use of force, but I got him detained safely. Figured out that he was 16 and autistic, and his mom just sent him to the mailbox, and then he saw a police car. It could have gone a lot worse, and it’s often difficult to know what’s going on initially.

I didn’t know a damn thing g about autism until a friend of mine started studying it. It’s fascinating and terrifying at the same time, mainly because it’s so poorly understood.

Before that I took a dim view of children “acting out” in public but one day my buddy says “That’s not a disciplinary problem, kid’s got autism”. Boy did I feel like a Grade A asshole after that.

Great article, keep ’em coming.

I am a family nurse practitioner, I have 2 sons with autism and they are at opposite ends of the spectrum. They both “line up” items near their eyes. Many autistic kids and adults will flap their hands up near their eyes,, it’s a similar thing. The area of peripheral vision at the outer corner of the eyes provides increased visual input to the brain. It has been explained to me that the increased stimulation can be a coping mechanism to “occupy” the brain and provide a sense of calm to some, or to others who are feeling detached or numb it may provide increased stimulation that combats a feeling of mental numbness. I read an excerpt from an autistic child who typed that he flapped his hands and arms and ran back and forth to “feel himself”, he would feel numb physically and doing ing movements to raise his heart rate would allow him to “feel” himself physically in space.

Excellent read, we police in Texas have crisis intervention training which is now geared largely towards handling the autistic and noticing signs. I have two homes for young adults with disabilities in my beat and the majority of them are on the extreme spectrum of autism.

It’s important that the public recognize that the role of an officer is broad. We are expected to be everything from crime fighters to social workers. Training and development is the future of police work.

One thing I’ve noticed as we turn our streets into open-air asylums is that we’re doing an absolutely shitty job of fitting our cops out to the be de-facto ward attendants.

If I got to be king for a day, and were given the power to make one change to how we do police work, the change I’d make would be to recognize this fact, and train accordingly. I don’t know what the percentages are, in terms of encounter, but I’ve seen way too many cases personally where the police officers in question were left completely at a loss as to how to proceed–We had a guy jump off a bridge, locally, just this last summer. And, he did it because the cops had had a report of someone behaving strangely on the sidewalk of that bridge, responded to it, and then simply by interacting with the poor bastard, precipitated him jumping over the railing. Honestly don’t know whether they could have done anything differently or not, but, still… I don’t think that they were handling the situation as well as they could have, from what I saw of the scene as I was driving by.

Of course, hindsight is 20-20; had they not surrounded the jumper, and allowed him to run off the end of the bridge instead of jumping, they might have basically left him to run loose into traffic or the neighborhood surrounding the end of the bridge, to unknown results. I don’t think they really keyed into the guys mental issues, at first–He was in the depths of a full-blown paranoid schizophrenic episode, according to the newspaper.

Fortunately, he survived the jump, although I’m damned if I know how–The spot he jumped from is like a 75′-100′ drop onto river rock.

Kinda feel sorry for the cops, too–I am pretty sure they didn’t want the guy to jump, and were simply not expecting him to vault over the railing the way he did.

As the phrase goes, though… Crazy people gonna crazy.

This is the best thing I have read on the internet in a long, long time. Good stuff.

You mentioned you would have told folks to back off in North Miami because you recognized the autistic guy holding things to his eyes, but I didn’t catch an explanation of what it signified. Was it similar to plugging ears due to sensory overload (like in your later example)? Thanks.

I really don’t know what it signifies. It’s one of the many things my son does that I don’t understand. I suspect it’s connected to the sensory stimulation or overstimulation issue, but I’m at a loss to really comprehend it.

Look up my friend Aaron Likens. He speaks to schools, LEA’s and even the FBI about Autism.