Sergeant Major David Stewart: Using this incident to make a positive change

[Continued from Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI, Part VII and Part VIII.]

In Iraq one of my friends screwed up at the beginning of a mission. After his humvee left the gate, he tried to load his Mark 19 grenade launcher. When he absentmindedly let the bolt slam forward the second time, the weapon fired; stunned, my friend realized he had just had a negligent discharge.

He ducked into the humvee and frantically shouted, “I accidentally fired two rounds!”

His vehicle commander asked, “Where’d they land?”

“I don’t know!” my friend yelled. “They haven’t landed yet!”

A few seconds later the rounds impacted. Fortunately they hit open desert, far from any people or homes. My friend was relieved, but knew he was about to get slammed badly for screwing up.

Instead, the vehicle commander calmly radioed, “This is 3, test fire complete.” And nobody said a word to my friend about his mistake.

When we soldiers step on our collective cranks, we have two ways of handling it. The normal method is to hide our mistakes, to pretend they never happened and hope nobody notices. In most cases, even our more egregious errors don’t leave visible scars; as with my friend above, if nobody gets hurt we can sweep our flaws under the figurative rug. But our other option is to publicly address our mistakes, to acknowledge our flaws before the people we’ve pledged our lives to defend. When our mistakes cost lives, the only honorable thing to do is own them, take the heat, and make changes that prevent similar tragedies in the future.

Option 1 is easy, option 2 is hard. Sergeant Major David Stewart has chosen option 2. And he’s using the Yusufiyah murders as the centerpiece of his efforts to publicly acknowledge the Army’s mistakes, to improve the Army from the top down.

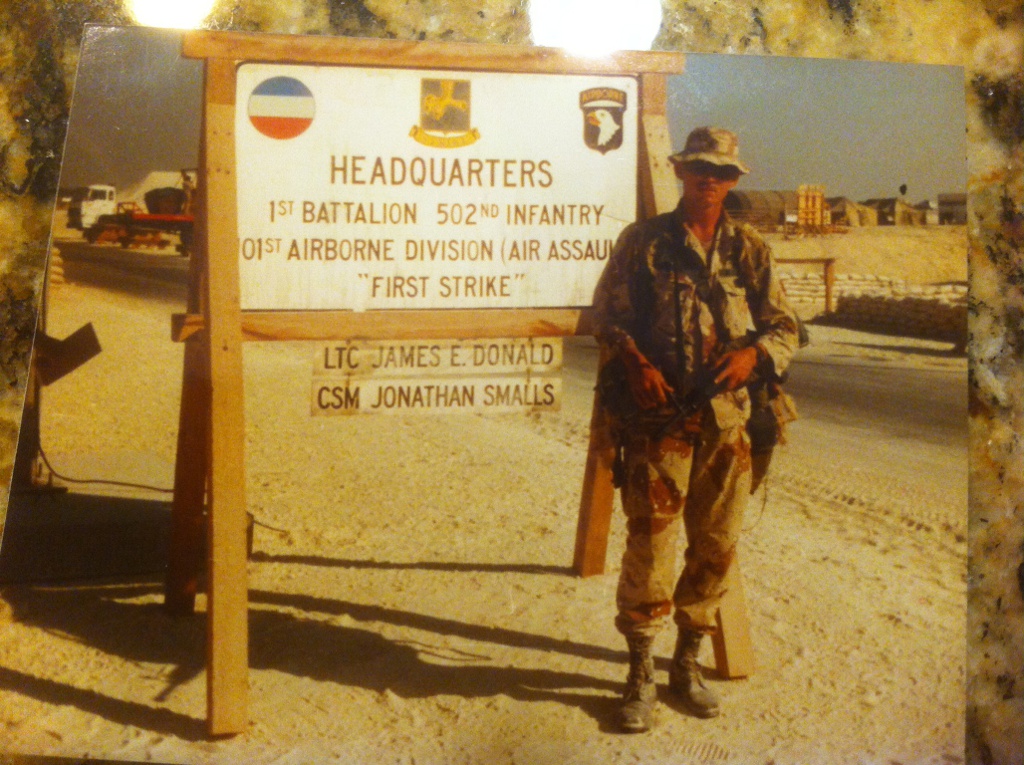

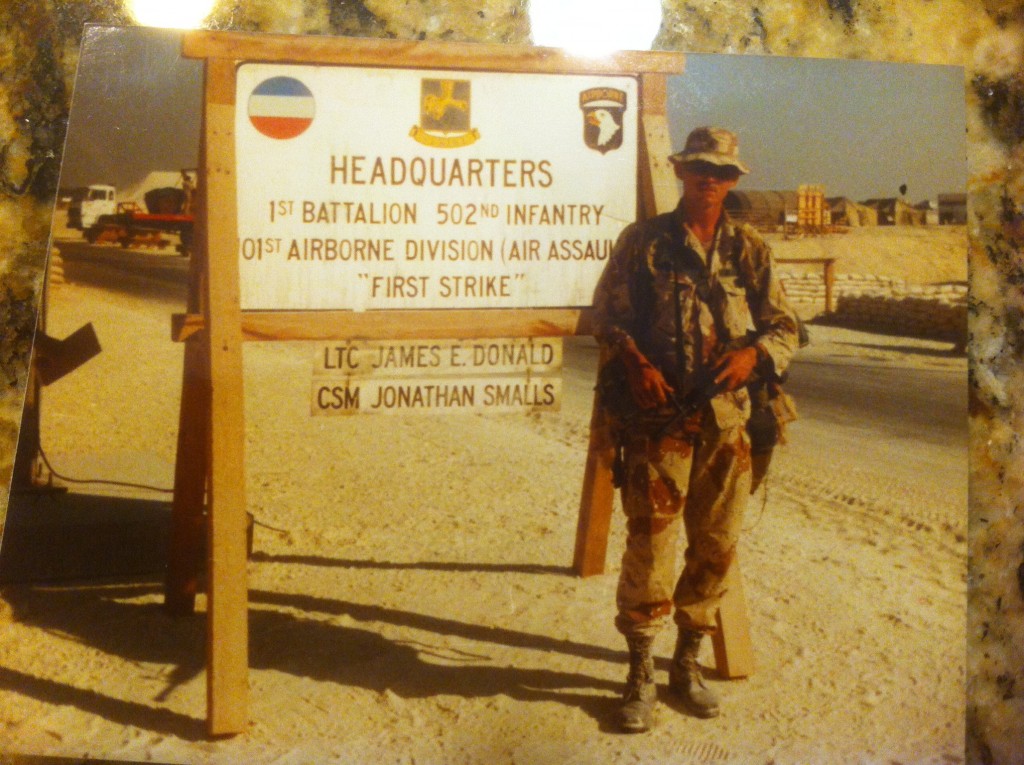

SGM Stewart heard about the Yusufiyah murders just before he started the Sergeant Major’s Academy. Like many other career military men, he was shocked that American soldiers committed such a crime. But the effect on him was worse, because the 1st of the 502nd Infantry was his home. “I started my career in that battalion. I served in it in Desert Storm and know a lot of the battalion’s senior leaders. I proudly wear a 101st combat patch.” For him, the story of the Yusufiyah murders was like a knife in the gut.

Not surprisingly, SGM Stewart takes his responsibility as a leader seriously. In one of our conversations, he quoted what seems to be his guiding principle: “The breadth of responsibility is a function of rank.” In other words, promotions don’t just equal better pay and benefits. If you’re going to accept higher rank, you must be ready for more responsibility. And one of our most important responsibilities as leaders is to ensure we and our soldiers follow moral standards. Even when we’re at war. Even when people are trying to kill us. Even when it’s hard and we don’t want to do it.

After he graduated the SGM Academy he deployed to Afghanistan for fifteen months, then returned to the Academy as an instructor. While assigned there he kept studying the Yusufiyah murders, and attended the Master Army Professional Ethics Trainer course. He incorporated more ethics training into the Academy curriculum, and co-authored a paper on loyalty.

Not long before he became Sergeant Major of the Army, SGM Raymond Chandler read Stewart’s paper. He was impressed. After he became SMA, he invited Stewart to join the Center for the Army Profession and Ethics (CAPE), a small organization focused on promoting ethical leadership at the institutional level. SGM Stewart became the organization’s senior enlisted advisor. Once settled in, he searched for ways to turn the Yusufiyah incident into a means to improve the Army.

After Bravo Company returned from Iraq, several soldiers in the company were asked to give videotaped interviews about the deployment and war crime. Watt, Diem and Lauzier had all agreed. SGM Stewart saw the videos, and decided to reach out to Watt and Diem to ask if they would help CAPE with its mission. Once he had their support, he set out to make the best possible use of their experience.

For the last two years, Watt and Diem have been appearing at CAPE events before specially-selected audiences. They’ve addressed cadets at West Point, the Association of the United States Army, and NCOs hand-picked by the Sergeant Major of the Army.

At many events Watt and Diem sit anonymously in the audience waiting their turn to speak. The audience usually doesn’t know who they are. Watt and Diem hear comments which are sometimes positive, sometimes not. At one event with a group of senior NCOS selected by the Sergeant Major of the Army, Watt heard a female Sergeant First Class comment that she’d never turn her soldiers in no matter what they did, because “snitches get stitches” (“I’ve never heard of a female rape apologist before,” Watt laughed).

During an event at West Point, Watt and Diem presented cadets with a hypothetical situation: what would they do if their battalion commander offered personal rewards for every confirmed kill a soldier made? They explained to the cadets that soldiers would be more likely to shoot when they didn’t need to, if they thought they’d get a pass or medal for it. The cadets agreed. Watt and Diem explained that such a policy would dramatically escalate the possibility of civilians being needlessly killed. The cadets agreed. So Watt and Diem asked, “How many of you would tell your battalion commander that offering a reward for a confirmed kill is a bad idea?”

Not a single cadet raised their hand.

But in addition to the occasional frustrating experience, CAPE has had spectacular successes. At one event, a senior NCO from the 10th Mountain Division was in the audience. His battalion had replaced the 1st of the 502nd after their terrible 2005-2006 deployment. Many people wrongly believe the attack on the Alamo that killed Babineau, Menchaca and Tucker was retaliation for the Yusufiyah murders, but when the enemy attacked the Alamo they didn’t know Americans had committed the crime. However, 10th Mountain soldiers were in fact targeted, abducted and killed because of the murders. In one of the most horrific events of the Iraq War, four 10th Mountain soldiers were killed and three abducted in an attack. The three abducted soldiers were tortured, in one case for months, before being murdered. The insurgents who carried out the attack emphatically stated they did it retaliation for the Yusufiyah murders.

After Watt and Diem’s presentation, the 10th Mountain NCO approached SGM Stewart and made a profound statement.

“Before this, I hated Justin Watt. I blamed him for what happened to our soldiers in Iraq. I thought if he had just kept his mouth shut those guys would still be alive. But now that I’ve heard his story, I understand. I know he did the right thing.”

SGM Stewart hopes this story gets through to all soldiers, the same way it got through, years late, to the 10th Mountain NCO. Although this program currently only involves senior NCOs and future officers, SGM Stewart plans on dramatically expanding it in the future. I asked, “Are you going to incorporate it into the curriculum as far down as the Warrior Leaders Course?”, which is the first school in the Army’s NCO educational System.

“No,” he answered. “We want to add it to all phases of training, from basic training onward.”

He wants ethics stressed all the way to the lowest level, because, as he says in his stern Sergeant Major way, “Both the commander and soldier are responsible for a mission, the welfare of their units, and the manner in which they fulfill their responsibilities.” Yes it’s up to leaders to provide effective, ethical leadership, but it’s up to soldiers to do the right thing even if their leaders fail. The training SGM Stewart hopes to implement Army wide will stress how important ethics in combat are for all of us, from boot privates to 4-star generals.

And SGM Stewart is trying to implement that training the right way. He knows most soldiers detest check-the-block PowerPoint “training”. Nobody wants to sit through a boring slideshow about sexual harassment or equal opportunity. Soldiers ignore most of what’s presented, the instructors are often bored victims who got “hey you’d” into being a presenter or, even worse, they’re passionate zealots who don’t understand why their audience is mostly asleep, and in the end very few people understand or care about the material presented. SGM Stewart is a twenty-plus year infantryman, and he knows he’ll lose audiences if he turns the Yusufiyah incident into typical mandatory training. He’s doing all he can to ensure this training stays interesting, and relevant.

That’s why he makes such a concerted effort to bring Watt and Diem to the presentations, because he knows they’ll bring the incident to life for the audience. Instead of being spoon-fed boring slides, soldiers hear firsthand the real, and really painful, experiences of two soldiers who lived through the unthinkable. Their stories always stimulate interest, and soldiers always leave with a new perspective. Watt and Diem have made more than twenty appearances so far. SGM Stewart is considering inviting other members of first platoon to join the events, to give their personal perspectives about the crime and what they think led up to it.

As a leader of soldiers, I understand just how important this kind of training can be. As I stated earlier, studying ethics in wartime doesn’t detract from combat training; it IS combat training. And if this training had been available to the men of first platoon before their deployment, maybe the Yusufiyah murders, and all their horrible consequences, would never have happened.

When I made the transition from National Guard into Active Duty US Army I saw a lot of contradictions. What I’m saying is that a lot of the Senior NCO’s E-6s & E-7 were overweight yet as an E-4 I was told to stay in shape according to regs. I have heard of APFT horror stories of people barely doing 10 push-ups and their buddy giving them a “GO” and some not taking it at all and getting a “300”! I’m old fashion and if I didn’t earn it don’t give to me. This is probably why I went ahead and got the honorable discharge for being overweight. I still LOVE the National Guard & Army – HOOAH!

Not sure how that relates to the Yusufiyah story, but hey man, I love the Guard too. 🙂

Y’all need to take a long, hard look at what the Israelis are doing in this arena. They’ve got some valuable stuff which we ought to be examining and perhaps, just perhaps, implementing some of. For those interested, do a quick Google of the term “Purity of Arms” in conjunction with “IDF”.

I remain convinced that a good deal of our problems dealing with PTSD and post-combat integration stems from a general reluctance to discuss this stuff openly, and not only from the standpoint of ethics, but of what we’re doing when we are going off to war in the first damn place. Nobody tells the young men and women we’re sending off so blithely into combat what they’re going to have to be dealing with, and how we expect them to conduct themselves in response. We don’t sit down and discuss the intricacies of what could be termed “combat ethics”, or explain the whys and wherefores of what we expect them to do. The whole thing is apparently supposed to be picked up by osmosis, or something. God forbid you bring up the implications of what it costs to kill, or the deep-rooted traumas you can pick up for dimes on the dollar when mistakes are made.

I was a combat arms NCO for 25 years. In that time, I can’t think of a single damn time that anyone ever really sat down and spelled out the the nitty-gritty of what we do: Kill other human beings. That’s the elephant in the room, the one everyone does their best to ignore, and the effects of this failure to openly discuss and train on this issue directly influence how our Soldiers cope with combat and deal with the after-effects.

I had the great good fortune to be exposed to some very smart, and introspective VIetnam-era vets when I was a young Soldier, men who’d been in some rather nasty places, and who were willing to answer questions I had. Some of them never had anyone ask them anything about their time in Vietnam, and I was the first to hear their words about what they experienced. Some of them were quite profound–One senior NCO told me that he’d gotten some excellent advice from his own father, a veteran of Normandy and the Bulge, who’d never discussed his wartime experiences with anyone, let alone his son. His dad simply told him this, before he left for his first tour in Vietnam: “Never do anything over there you won’t be able to sleep with when you’re fifty years old, and remembering things… I sleep well at night. A lot of my friends from back then didn’t, and that’s why they’re not here anymore…”. Which was when my old Platoon Sergeant remembered just how many of his father’s peers either drank themselves to death, killed themselves, or just plain died young from misadventure.

The Code of Conduct is great, if you plan on becoming a POW as a part of your battle plan. What it signally fails to address is how you should conduct yourself as a Soldier in combat, and what your responsibilities/duties are in that mode. Young men need these things, and we should have a Code of Conduct that addresses those needs clearly and emphatically. Not only would such a thing provide them with a touchstone for times of moral challenge, it would serve to inoculate them against needless guilt over what they have to do in order to survive. The value of such a code is something I don’t think we consider carefully enough.

The Navajo Indians had an interesting set of customs surrounding the sending off of young men to war: There was a ceremony that carefully marked off when they were leaving normal life, and going off to war, and another purification ceremony when they returned from it, to cleanse them from the responsibility and guilt for what they had to do while at war. These are not just silly customs of the primitive–Such ceremonial traditions have value in that they allow a young man to clearly differentiate between what he did while at war from his normal life, and enabled him to overcome the onus of having killed others. As well, it served to tell the young man that he had the support of his society in what he’d done–Something the average Vietnam veteran did not get, to their general great detriment.

Kirk,

Very interesting comments and perspective, thanks. You reminded me of something I read on Weaponsman.com, a story of a veteran who had a very squared-away, motivated female soldier in a medical unit. She was Hindu, I think originally from India or of Indian ancestry. After qualifying with her weapon she approached her NCOIC with a horrified look on her face and said, “Someone just told me those targets we’re shooting represent people! Is that true?” And the NCOIC had to explain that qualification was, in fact, training to shoot people. The veteran telling the story wondered how our recruiting and training practices could be so bad that a soldier could get past basic and AIT and still not know we’re training for actual war.

Personally, I blame a lot of it on our recruiting efforts. For decades the Army has emphasized Learning New Job Skills/GI Bill/Army College Fund/Anything But War in its commercials. I can only remember seeing two Army commercials over the last 20 years that focused on combat, and one of those was a National Guard commercial. So we recruit people who really don’t think they’ll go to war, and really aren’t prepared when they do. The Marine Corps, on the other hand, focuses on being a warrior. And that works better.

That was me, over on Weaponsman. And, that really happened, incredible as it may seem.

Completely blew my mind at the time, too. Still does, as a matter of fact. We’re doing something wrong, fundamentally wrong, when something like that is even possible.

And, what’s screwed up about that whole deal? She was a great Soldier, worked hard, PT’d her ass off, did all the right things, self-motivated, self-disciplined, and what I’d point to for any of my other young troops to copy.

Just one, teensy-eensy little problem, though… Devout, practicing Brahmin. Who we recruited, and then never bothered to mention anything to about our root mission, ever. I’m dead serious about that whole thing–It really happened, and she went through Basic and AIT at Fort Leonard Wood (if I remember right, about the Basic location–She definitely went through FLW for AIT as a draftsperson) after 9/11.

I honestly think the problem originates in how we recruit, how we train, and how we handle everything about talking about what we do. There is a huge volume of knowledge about this stuff, but we don’t bother to apply it.

Go back to WWII, and look at how carefully the Germans managed their training and replacement programs, and then compare it to what we were doing with individual replacements fed in from depots, like they were so many inanimate parts. We kept doing that stupidity right up until 9/11, and the vestiges of it are still with us. It doesn’t work, and it’s highly destructive of our personnel assets.

I honestly believe that a combat unit should not be touched, either by changing commanders or troops, until at least six months after redeployment, long enough for any issues stemming from combat stress to manifest themselves. I’ve watched too many guys who burnt themselves out while in theater be destroyed by chains of command and peers who had no fucking clue what they’d been through, or that they might need help. Moving someone who’s barely keeping it together from his home unit to “somewhere else”, where he or his experiences aren’t known is just plain stupid. Likewise, putting a brand-new commander into a unit freshly returned from combat, who has no idea what his men have been through? Equally stupid.

You stop and look at it, and it sometimes seems like everything we do is designed to maximize the potential for long-term combat stress and PTSD, not to mention increasing the risk of things like what happened in Yusifiyah and in the Maywand District killings–Which are, themselves, another fit subject for research. I watched that brigade stand up, and it was a cluster-fuck of the highest order–Hordes of unsupervised lower enlisted, no leadership for months, and probably the highest rate of indiscipline I’ve ever seen during that period. It didn’t come as a huge surprise when those guys had the tour they had in Afghanistan.

Some of our guys went over there, and the horror stories I had reported back to me were insane–One of my junior, newly-promoted Sergeants went over there, and wound up serving as a friggin’ Platoon Sergeant while the real one was at ANCOC. He was riding herd on about thirty-forty brand-new, fresh-from-AIT troops, and the crap they were getting up to was mind-blowing. Straight out of the 1970s–No adult supervision, and what they had was over-worked and lax as hell. Of course, all I saw was as an outsider, talking to former subordinates who were over there, but the trends which finally manifested in the Maywand thing were there from the beginning.

The US Army does not pay attention to the “minor issues” of small unit and primary group formation and culture. You don’t just put all the requisite bits and pieces of a unit into a bag, shake it up, and expect a high-quality unit to step forth from the forehead of Zeus like Athena did. It does not fucking work that way. Organizations are separate, discrete organisms, and they don’t “just happen”. You go back in history and look, and just about every single time we’ve had issues with this shit, it came from a unit that was thrown together at the last minute. My Lai? 23rd ID, the Americal. Formed up out of elements already in Vietnam, and never really quite “got it together”.

Unit formation is a lost art, I’m afraid, and we’re not doing it right. I really think that a better way of doing business would be to plus-up the living hell out of an existing, functional unit, and then form the new unit by fissioning the old one. That way, there’s continuity of unit culture and operating procedures, and less likelihood that there will ever be junior enlisted running around at loose ends. That’s just a recipe for ‘effing disaster.

We also don’t pay careful enough attention to what the hell some of our leaders are up to–Reports I’ve heard said that SSG Gibbs was manifesting clear “problem child” issues when he was in the Brigade Commander’s PSD, and they pawned him off on the line unit he was in when the crimes were committed without a word of warning about their concerns with him.

That particular Brigade Commander struck me as being much like the guy who commanded in the Yusifiyah situation, being both dangerously arrogant, and very detached from reality. He’s the one who basically said “Fuck this BS from the theater commander, I’m fighting my own war, here…”, and the attitude was clearly communicated in the unit down to the lowest level. I have no idea if things would have gone better with them if they’d have gone to Iraq as they were originally slated to, or not, but the attitudes and arrogance demonstrated by the command before deployment tell me that they probably would have had similar results.

Do note the interesting coincidence of where SSG Gibbs was assigned, prior to his arrival in Bravo Company. He’d have had ample opportunity to hear COL Tunnell speak, and absorb his attitudes. Not enough attention was paid to this during the trial proceedings, in my opinion. Couple of the guys I know from over there were quite adamant that there were several “unindicted co-conspirators” in the Brigade chain-of-command who should have been in the docks with the rest of the so-called “Kill Team”.

And, if I recall correctly, COl Tunnell was very well thought-of, and just about a shoo-in for his star before all the publicity. Kinda makes you wonder about the whole promotion system, when you realize that. He’s got some good publicity, that’s for damn sure. Too bad I can’t say I ever saw anything that supported it, from outside his unit. The way our guys were treated and managed over there, I’d have done whatever it took to avoid being around that whole crew–There was a clear aura of toxic leadership in that brigade, right from the beginning. At least, from my perspective. I’m sure someone else might have had a different viewpoint–Tunnell did have charisma, and some true believers following him. I think SSG Gibbs might have been one. The results sort of speak for themselves, don’t they?

Kirk,

I actually wondered if you were the guy from Weaponsman, but thought. “Nah, it couldn’t be.” 🙂

What you said about the Army basically enabling PTSD reminded me of something I’ve said in the past about the way Guard units deploy. We get thrown together from various disparate units, have a few months of shitty training, deploy, then come home and get scattered back to our home units. That’s pretty similar to what happened to soldiers after Vietnam.

I need to look into the Kill Team story. It sounds like an absolutely fucked-up situation, and in the trailer I watched for the documentary I heard one soldier say something like “I did what I was trained to do and they charged me with murder”, which is self-serving bullshit.

I should probably email you instead of cluttering up the place with my posts. I do tend to rant, and my reply to this went on for just a wee bit…

Kirk, I really enjoy reading your rants. I think I learn a lot from the experiences you share, so please keep on sharing both here and over at weaponsman!

This was absolutely one of the best unbiased written articles that I have read in a very long time. In my opinion the article points out what’s very wrong with the military and in almost the same breath what’s very right about the military. I’ve often said I met the some of the very best of mankind and some of the the very worst of mankind while serving in the military. Reluctantly my experience with most, but certainly not all military leadership is best summed up by “the emperor has no clothes”….

Thanks Jimmy. I’m not the kind of guy to pretend like everything in the Army is perfect, and I think the only way to properly handle a situation like this is to hit it head-on.

I’m also old for my rank, and have no desire to ever get promoted again. That might make honesty a little easier for me. 🙂

It’s great that SGM Stewart is doing what he is doing. But the Moral of the story is that high ranking bad leadership gets a pass. We can talk about values, we can talk about the right thing, but bad senior leaders will continue to be bad until they are held accountable. LTC Kunk is now COL Kunk. Shouldn’t that tell you something about where the problem lies?

That’s actually a point I was going to make in the last chapter. This series isn’t only an indictment of individuals, it’s an indictment of a system. Why do I indict the system? Because the men involved were punished, leaders up the the company CO were removed from command, but the BC was promoted. I don’t know how that can indicate fairness within the system.

I would have skull dragged that NCO who said “snitches get stitches”. People nowadays fail to realize that they are part of an organization. Despite what the Army is doing today, its not about an individual. That NCO is a future toxic senior leader. There is handling stuff at the lowest level, then there are incidents like this. The 1SG shouldn’t have to worry if Joe is getting paid correctly because he has Platoon Sergeants, Squad Leaders, and Team Leaders. But something that affects the very moral fabric of the values we live by everyday is something we need to let be known.

I’ve been seething on exactly this point from the beginning of this series. I was going to bide my time before opening that can o worms but “Inked” beat me to it with his (very appropriate) comment. Truth be told, good men can do great things in regards to preventing this in the future. But until there are heads on pikes for having created the disastrous environment that spawned this chain of events, there can be no true healing. So long as the Army pursues the symptom and not the root cause, this infection will continue to fester.

I look forward to your next installment.

This is a sad fact about the story…why wasn’t that leader reprimanded and asked to leave the Army? Why is he promoted??? although I don’t know his side of the story…what I’ve read so far has my head spinning.