Mad Duo Minion + a handful of Coalition troops vs. all the Taliban in the world.

Thought that would get your attention. You know what today is? Today is March 14th, the five year anniversary of when our minion “Mad Duo Chris” Hernandez, alongside French and Afghan troops, pretty much defeated one million Taliban. Here’s the story. Mad Duo

Afghanistan was Therapy for Iraq

When I came home from Iraq, my father asked me if I had been in combat. I answered, “Yeah, I was.” But inside, I wasn’t really sure.

Yes, I had been shot at. Sort of. My convoy escort team took sporadic small arms fire which never hit anything, not even the huge civilian-driven 18-wheeler trucks we were protecting. Once someone hiding between cars on the side of a road fired a blast of birdshot into the windshield of one truck; nobody was hurt, and I didn’t even know about it until we arrived at our destination. We never identified a target, never returned fire. I’m pretty sure my gunner engaged a car bomb one night, but I’ll never know for certain if the man was trying to ram us or was just a stupid driver.

My team had IEDs go off a ways in front of us, and a short distance away on the side of the road beside us. Once a convoy on the other side of the highway from us took an IED strike. On another night a truck from another convoy was blown up about 25 meters behind my Humvee. Rocks were blown all over my vehicle, but there was no shrapnel, no damage, no casualties. On a later mission my team passed another convoy team headed the opposite direction. Less than three minutes after we passed them, they screamed on the radio that they were in contact. I was riding gunner that mission, and had been ready and eager to finally return fire. But once again, it hadn’t happened. I ducked into the Humvee and yelled in frustration, “What the F**K? We were just there, nobody shot at us!”

On yet another convoy, Anbar Province, Fall 2005

I fired four shots from my carbine during my Iraq deployment, two warning shots and two more trying to scare a herd of camels off the highway. They weren’t impressed. I was awarded a Combat Action Badge for a mission where a car bomb destroyed a Humvee way ahead of us, and an IED went off in front of us, and a convoy that stopped right behind us engaged in a brief firefight. I had the crap scared out of me numerous times by suspected IEDs or car bombs. I was always on guard for the sudden explosion that could kill my entire crew but never did, always searching for the firefight that I was never in. I was in constant danger, but never in what I considered a real fight.

So I was in combat in Iraq…I guess?

Iraq scarred me. No, not with PTSD. But when I came home I was tense, irritable, angry at the impossible situation the Army I loved had put me in. I was strung out from the hundreds of Cokes and Red Bulls I had drunk to stay awake on missions, and dependent on the Benadryl I had used every day to counteract the caffeine. I was, to put it mildly, stressed. I had volunteered to fight in Iraq, but wound up an expendable cog in a logistical machine. The painful truth is that I had felt helpless in Iraq. My pride and skill as a tanker had counted for nothing as I performed a frustrating and seemingly needless support mission I had never even imagined before being mobilized. On most convoys I had risked my life not to provide critically needed ammunition or fuel, but to keep the DFAC stocked with steak and lobster. I could have been killed or crippled just to provide creature comforts. I was mad, and if I had gotten out of the Army after Iraq, I would have stayed mad.

But three years after I came home from Iraq, I was in Afghanistan. And early in my Afghan deployment, five years ago today, I found myself in my first, heart- pounding, adrenaline-pumping, don’t-know-if-I’m- gonna-live-to-see-my-newborn-son, actual battle.

On the objective and smiling during a lull between contacts in the Alasai Valley, March 14th 2009

I learned a few things from that battle. I learned that real combat isn’t like any movie I had seen; i t has peaks and valleys, moments of pandemonium and minutes of excruciating boredom. I learned that after vicious exchanges of fire, Soldiers will stand around in the open as if nothing just happened. I learned that many troops in battle will routinely display what would be considered unbelievable bravery back here. I learned that most Soldiers don’t dread combat, they eagerly seek it.

And I learned something else. I didn’t realize I knew it until I talked with a friend years later. He had been in my battalion in Iraq, on the same convoy escort mission. He then spent a year in Afghanistan on an Embedded Training Team. And he said something that made perfect sense, and captured exactly how I felt.

“Afghanistan was therapy for Iraq.”

One day of combat in Afghanistan made up for the year of fear, frustration and helplessness in Iraq. It erased the anger I felt at being a “designated IED target”, of feeling like the Army was willing to sacrifice me in order to ensure a steady supply of ice cream, video games and gangsta rap CDs at the PX. It even made up for years of what sometimes felt like pointless peacetime training, for all the days and hours I spent preparing to fight wars long past.

On March 14th, 2009, French Mountain Troops, Afghan soldiers, a handful of other Americans and I invaded the Alasai Valley in Kapisa Province, and defeated ONE MILLION (or a hundred, I’m bad at math) Taliban fighters. For this first “real” battle, I was attached to a Marine Corps Embedded Training Team, attached to the Afghan Army, fighting alongside the French Army. I was asked to command a Marine Humvee, and chose to command it from the turret. As gunner, I had a perfect view of our five-kilometer – long rolling asskicking; a column of tanks, armored personnel carriers, Afghan Army pickup trucks and infantry on foot relentlessly machine gunning their way into what had been inviolable Taliban heartland.

French anti-tank missiles flew overhead and slammed into enemy compounds. Mortar rounds fell from the sky onto enemy positions. A-10s made gun runs and dropped bombs on distant mountainside target

s. Apaches and Kiowas flew crisscross patterns above us. The enemy fired, fell back, regrouped, and kept fighting. We ducked, swallowed the likelihood that an IED would destroy at least one of our vehicles, and advanced.

The atmosphere inside my Humvee was cheerful. We sang. We made jokes. We fed off each other’s energy, enjoying what was probably the most intense moment any of us had experienced. I made contented peace with the possibility of my death. We scanned for targets and struggled to decipher every frantic radio transmission. We watched Afghan soldiers milling in disarray and heard the frustrated curses of their Marine trainers. And we kept rolling into the valley.

When we reached our objective, the fight wasn’t over. We traded shots with unseen enemy. A sniper barely missed me, twice, then shot my gun shield and stopped firing. An Afghan soldier used a wall around a government building as cover and blasted eight or nine RPG rounds into a compound; the backblasts blew out some of the building’s windows and convinced a nervous Marine that mortar rounds were landing in the courtyard. I used my Humvee as rolling cover for a group of Marines and a corpsman so they could reach a wounded Afghan. Later that evening, the Taliban launched an attack that turned into an hours-long, raging fight. A rocket missed my vehicle by mere feet. A French tank’s muzzle blast rocked my vehicle and filled it with smoke and dust. During a period of relative calm, I watched French troops, standing tall and proud, protected only by darkness, carry a fallen brother from a burned-out vehicle within 100 meters of enemy. And I think I killed someone that night with a long burst of .50 caliber fire.

Holding a good luck charm my oldest son made for me, next to the damage from a sniper’s bullet. Ignore my gut, it’s an optical illusion.

The battle was confusing. The sensory input was overwhelming. Death was moments or inches away. And right or wrong, I loved every second of it. I was finally a Soldier, in real combat, doing what I was born to do. The wounds inflicted in Iraq were healed.

Five years ago today, I achieved one of my life’s goals. I stood with my brothers against the enemies of our great nation. I felt fear – real fear – but discovered that I could perform my duty under fire. I witnessed the almost casual courage of men who don’t just talk about honor, but live it. I experienced the privilege of righteous combat, against a worthy enemy, alongside the most dedicated of men. I wasn’t victimized by this experience, I asked for it. And I treasure the memory.

I was in other fights after Alasai. Only one was as intense, but on a smaller scale, and with a tragic conclusion. In another engagement late in my deployment, I accompanied French Marines as they surrounded, pinned down and wiped out a small enemy force with sniper fire and air strikes. I had other victorious moments and developed other strong bonds of brotherhood, especially with the French Marines snipers. But nothing else I’ve experienced, before or since, approached the triumph of the Alasai Valley.

I suffer no illusions about the impact of our victory. Yes, it was an amazing experience at the personal level, perhaps even noteworthy from a historical standpoint. But it didn’t change the nature of the war, the country or the Afghan people. Our actions likely had no effect on the ultimate outcome. But regardless of what is sure to follow after we withdraw from Afghanistan, on that day, on that mission , we succeeded. We achieved something momentous. And if we can’t find worth in the end result, surely we can still accept – we can choose to believe – that our shared valor wasn’t wasted.

March 14th will always remain a solemn day for me. But it’s not a day of mourning, it’s a day to celebrate. It’s a day to remember the accomplishments of what our coalition was when we were at our best. It was the day I felt worthy of my great uncles’ service in World War II and Korea. It’s the day I began to be cured of what convoy missions did to me. Five years ago today, Afghanistan became my therapy for Iraq.

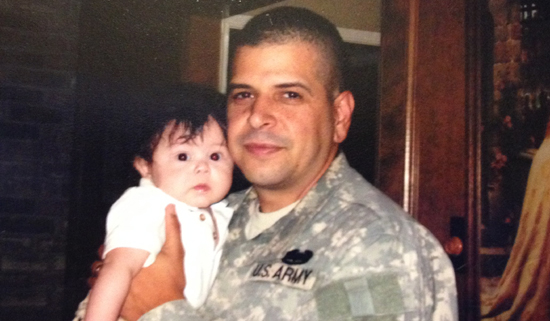

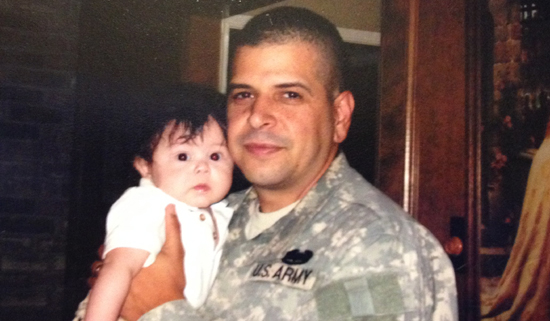

Meeting my newborn son Lucas for the first time, three months after Alasai. Yes, my first words to him were “Luke, I am your father.”

Chris Hernandez (Mad Duo Chris, seen below on patrol in Afghanistan) may just the crustiest old member of the eeeee-LIGHT writin’ team here at Breach-Bang-Clear. He is a veteran of both the Marine Corps and the Army National Guard who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also a veteran police officer of nearly two decades who spent a long (and eye-opening) deployment as part of a UN police mission in Kosovo. He is the author of White Flags & Dropped Rifles – the Real Truth About Working With the French Army and The Military Within the Military as well as the modern military fiction novels Proof of Our Resolve. When he isn’t groaning about a change in the weather and snacking on Osteo Bi-Flex he writes on his own blog, Iron Mike Magazine, Kit Up! and Under the Radar. You can find his author page here on Tactical 16.

Mad Duo, Breach-Bang-CLEAR!

0 Comments