Continued from Part 1 and Part 2.

Departure, Return and Loss; Part 3 of 3

Nate Murr

The man no longer carries a gun for a living, but he has one near at all times. His new girlfriend wonders why he changes lanes on the highway when there is an old tire or pile of trash on their side. Sometimes at night he wakes up in a cold sweat, sometimes screaming or shouting orders to other men whose names she doesn’t know. His quest to find a better job has been futile but he is happy to have the one he has. After the first few months of living at home with his parents, he’s tired of being treated like a child. His mother looks at him like he is a stranger, and his father doesn’t know what to say to him anymore. After dozens of awkward interviews, he found a low paying job that he suspects was given to him out of pity, but at least he could afford his own place.

There was no parade for his homecoming, not that he expected one. It has surprised him that so few people seem to recognize, let alone care, that there is still a war on.

The friends he grew up with, the ones he missed during his early years away, have moved on with their lives. Many are married and have kids. Others are divorcing or live wherever their degrees took them. The man has made a few new friends, other vets he met through mutual friends or while drinking at the bar. Often these are the only guys he feels he can talk to, but that bothers him.

He feels like a complete failure. He battles the VA, trying to enroll in school next year, and he dreads his daily, dull routine. He has learned to keep his mouth shut about the war. Nothing positive come from him speaking about it at work or in public. A Vietnam vet recently told him, from the barstool next to his that it “…gets easier with time” and that he should “…talk about his experiences” with people. The man isn’t certain that either of those pieces of advice are necessarily true.

He gets late night phone drunk calls from other guys that got out, old buddies from his first deployment and now more frequently from guys from the second deployment. Some talk about trying to go back in, but that’s unlikely to happen with the troop downsizing. Others just want to talk about the old days, which often leads to both sides of the line crying. Promises are made to visit each other. Sometimes they actually do. One day he gets a call from a friend, informing him that their mutual buddy has committed suicide. After taking off work to drive out of state to attend the funeral, the man feels more cold then he has ever before. He wonders why his friend killed himself, but part of him sort of understands. It bothers him, because he knows he has thought about it himself.

The world that he lives in is not the one he remembers, and certainly not one he has envisioned. He feels alien in his own hometown, among the very people he had missed for so long. Now he is an outsider, a burden, a failure at life and as a man. He thinks about all that he had to survive, just to make it home to what? This? An ungrateful, unsupportive nation that doesn’t care about him, or his friends? All the death and loss, the suffering and fear, for what? So he can enjoy a life trapped in a shitty job, with no prospect of advancement and no feeling of accomplishment? Everyone looks at him like a broken man, and everyone treats him like a victim. No one understands but the guys he served with, and even then they look at their lives now differently.

He wonders that maybe the ones that opt out are the ones with the right idea.

Unfortunately, this sort of story is a fairly common one, though by no means the only one.

The experiences and perspectives shared in this fictitious narrative are based off the thoughts and feelings many combat vets go through. The hard part is not hardening boys into strong men, nor it it the training of them for war. I’ts not even the toll that it takes on them, having them fight and endure so much. For far too many of them it’s coming home that’s the hardest part. It is after the uniform comes off, when veterans try to make a go at what they have earned (a happy, healthy and successful life) that the most difficult struggle of all begins.

Suicide for those both still in the service, as well as those who’ve left the military, has drastically risen. It remains a heart wrenching issue and is one that needs to be properly addressed, and reduced. There are many ways you can help and most are pretty simple. Start by caring. Show that you care about veterans while they are still in the service. Send letters and care packages to those that are deployed. Support your local veteran organizations and foundations. Stop thanking them for their service, and SHOW them that you are grateful for their service. Make these men and women feel appreciated, and show them that you actually care. Be a mentor to the younger vets coming home, help them find good jobs and support them in every way that you can. Give them your time because if you do, it is buying them the ability to move through one of the most difficult transitions of their life. Do not broadly label all vets with the social stigma of PTSD, and if they are suffering from it don’t treat them like victims. The healing and recovery of this long and brutal war is going to take time and effort. Without the support of everyone here at home, some wounds will never heal.

Together we can reduce veteran suicide and build a culture of pride for our warriors.

Mad Duo, Breach-Bang& CLEAR!

Comms Plan

Primary: Subscribe to our newsletter here or get the RSS feed.

Alternate: Join us on Facebook here or check us out on Instagram here.

Contingency: Exercise your inner perv with us on Tumblr here, follow us on Twitter here or connect on Google + here.

Emergency: Activate firefly, deploy green (or brown) star cluster, get your wank sock out of your ruck and stand by ’til we come get you.

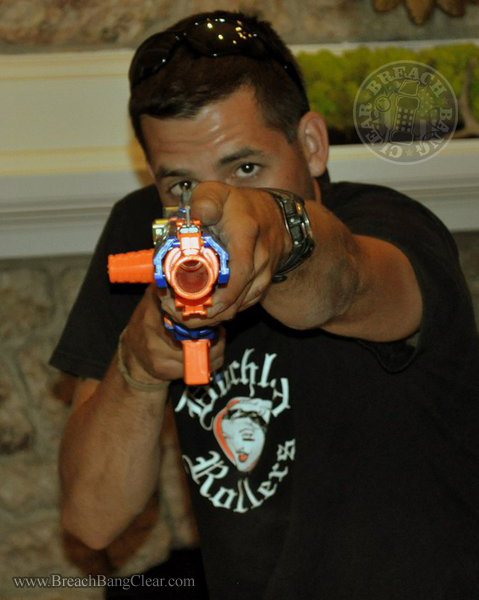

Mad Duo Nate

My steps to getting healthy:

1. Talk to someone who understands about what went on downrange, and about your struggles coming home. For me, this was two or three good buddies who’ve been downrange.

2. Do something with your life that makes a difference to someone. I’ve replaced roofs for single mothers and elderly widows, fixed cars for friends, taken my kids to help clean the church, taught basic marksmanship to a kid whose father walked out on him, etc. Nothing gives you a sense of purpose and makes you feel like a hero to someone like helping good people who are in a jam and can’t help themselves.

3. Develop a relationship with God.

4. Work towards being the man your wife and kids deserve for you to be. Even if it means going to a shrink. Even if it means changing smelly diaper number 45,502.

5. Do personal development. Martial arts, college classes, hobbies, anything that makes you feel like you have a direction with your life.

Talking about what you went through is important, but it’s only part of being healthy. Talking helps us organize our thoughts, understand what we’re feeling and why. It can give us clues to help us get through our pain.

You need to talk about what you went through, but with the right people. You talk about it because it doesn’t just help you, it helps other guys as well. If they can get their pain off their chest, it can help them, and keep them from killing themselves.

After I got back, I decided to be candid about the things I went through with my wife and with other vets; command screw-ups, dead friends, etc. I’ve had several friends come to me and tell me, “Remember when we were talking about X? Yeah, I was thinking about putting the gun in my mouth. I might have done it if you hadn’t been there.” I’ve even had a few women ask me about PTSD only to find out later that my candor had helped them with having been raped.

I had days where I felt so broken I thought I’d end up alone; I thought my wife and kids were going to leave me and never want to see me again. But if you find a direction for your life, work on self-improvement, talk out your problems, help others and get a relationship with God, it gets better. It can be better than you can imagine. But it takes time, humility and work.

Stick with it.

Just read this while at the house. The only thing I could add is that he wonders what happen to the friends he made over there. Are they alive? Also why does it feel like he never really came home fully, why does it feel like a part of him is still at war or would rather be at war?