Sometimes we like talking about men who were hard as woodpecker lips and unabashedly good at killing people who needed killing. This is another one of the men who had a bucket of balls and backbone like a boss. -Mad Duo

Bucket o’ Balls and Backbone Like a Boss: Pete Ellis

Bucky Lawson

Most Marines have at least heard of Lt. Colonel Earl Hancock “Pete” Ellis. It’s common knowledge in the Corps that Ellis predicted the war with Japan and how it would be fought, and that he laid the foundation for what would become the American amphibious juggernaut of World War II and beyond. Far fewer, however, know the story behind this remarkable and tragic man.

Ellis is also almost unknown outside the Marine Corps, and that’s a shame, because he was one of the foremost military thinkers and innovators in our history. I’m not going to roll out a full bio on Ellis. That’s already been done. What I am going to do is hit some high points to promote interest in a man whose work is still relevant nearly a century after his somewhat mysterious death.

From Counter-Insurgency to the Trenches

Pete Ellis was born in Kansas in 1880. In August, 1900, inspired by newspaper stories about the Spanish-American War, Ellis took a train to Chicago and enlisted in the Marine Corps. He made corporal in February, 1901 and hired a retired Army colonel to tutor him for the officer exam, which he passed, earning his commission in December. His first overseas posting was to the Philippines, where he served two tours by 1911, assigned as a company commander under Lt. Col. Joseph H. Pendleton and Gen. John A. Lejeune.

You might recognize those two names.

Ellis took part in putting down the Philippine Insurrection, which erupted soon after it became clear that Uncle Sam wasn’t in any hurry to grant independence to the archipelago. Ellis served with distinction and later published an article on counterinsurgency for the Marine Corps Gazette, which appeared under the title “Bush Brigades” in 1921. Though the terminology was different, Ellis proved to be an astute observer of COIN ops and his work dealing with policy and tactics holds up well against what’s being published today.

Awaiting air support on Eniwetok. Photo Credit: https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/III/USMC-III-III-5.html.

In October, 1917, Ellis, now a major, was sent to France on a liaison mission in preparation for the arrival of Marine units in Europe. Ellis was disappointed because he had requested a combat assignment. Lejeune was dispatched to France in May, 1918 and eventually took command of the 4th Brigade (Marine) AEF, consisting of the 5th and 6th Marines and a machine gun battalion. Ellis became the brigade adjutant, essentially what is known today as an operations officer. The brigade eventually made up half of the 2nd Infantry Division.

Ellis gained a reputation as a capable planner and he stayed in that position through the end of the war. There is occasional confusion about the official relationship between Lejeune and Ellis after the former’s promotion to command the 2nd Infantry. Lejeune appears to have relied heavily on Ellis but there is little in the way of official evidence as to the nature of that reliance.

What does seem apparent is that Ellis had a major influence on the 4th Brigade (Marine), especially after Lejeune’s promotion. Brigadier General Wendell “Buck” Neville, a future Commandant of the Marine Corps, succeeded Lejeune as commander, but Ellis, now holding the temporary rank of Lt. Colonel, loomed large. Thomas Holcomb, commander of 2nd Battalion 6th Marines and another future Commandant, said that Neville “…held the title, but Pete ran the brigade.”

Marines on Tarawa. Photo Credit: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/202591683209571273/.

By this time, however, Ellis had become a heavy drinker, prompted by frequent bouts of depression. He would sometimes be unfit for duty for days at a time, but an anecdote from this time shows how highly Ellis was thought of by Lejeune. Just before the 2nd Division’s attack on Blanc Mont in October, 1918, Lejeune had promised the French that his division would take the heavily-fortified position in return for not being split up as replacement brigades. After making that promise, Lejeune, trying to figure out how to make it happen, reportedly called for Ellis. Informed by his aide that Ellis was “indisposed,” meaning that he was drunk, Lejeune supposedly replied “Ellis drunk is better than anyone else around here sober.”

There is some confusion about who actually made the statement, since Holcomb says it came from Neville, and Ellis’s biographers say it may not have happened at all. Either way, Ellis was a shrewd and proven planner and one of the more intelligent officers in the Corps. He was obviously effective, even with his drinking problem, or he wouldn’t have had the job at that point. His service was exemplary enough that, even though he never held a command slot, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, the Navy Cross, the French Croix de Guerre with Gold Star, and Legion d’Honneur (Chevalier). You decide.

Lejeune himself, years later, attributed the division operations plan to Ellis, though this is disputed by most everyone else and no evidence exists to support the claim. Whether Ellis had a hand in its planning or not, the (successful) assault on Blanc Mont, cost the Marines more casualties in a single day than any of their other engagements in World War I. Some believe that Lejeune carried a feeling of guilt over Blanc Mont the rest of his days and that the indictment of the long-dead Ellis was a way to ease some of that guilt. While he may have advised in some capacity, there is no official evidence that Ellis planned anything above the brigade level.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Doctrinal Groundwork for the Next War

Ellis is most famous for his contributions to American amphibious warfare doctrine. He’s basically the Godfather of US amphibious capability. As early as 1911, Ellis predicted future naval wars against Germany and Japan. Such a prediction wasn’t terribly unusual, considering Germany’s saber-rattling in Europe and the rise of the Japanese Empire in the Far East. What set Ellis apart from other would-be strategists was his clear vision of how the war in the Pacific would be fought.

After bouncing around various assignments after the war, during which time his alcoholism got worse, Ellis was given an assignment by Lejeune, now Commandant, which influences amphibious doctrine even today. While serving in the Philippines, Ellis had been briefly attached to an advanced base unit. A 1911 report to the Commandant attributed the top-notch condition of the advanced base outfit in the Philippines to the “…excellent work of Captain Earl H. Ellis.”

The Advanced Base Force was a relatively new idea. Its purpose was to secure and defend advanced fleet bases for the Navy to operate far from home. The need for this force had arisen when the US took possession of the Philippines and became responsible for their defense. The Advanced Base Force was to occupy and maintain suitable coaling stations and anchorages for the fleet while also denying them to any potential enemy. As early as 1897, the likely identity of that enemy was clear: Imperial Japan.

After returning from the Philippines in 1911 Ellis had attended the Naval War College, where he engaged in the development of the emerging War Plan ORANGE, which dealt with the projected war between the US and Japan. There he refined his ideas about the role of the Advanced Base Force in relation to the plan. His performance was good enough that, like Maverick in Top Gun, he was kept on as an instructor at the request of the college commander.

Air Support on Eniwetok. Photo Credit: https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/III/USMC-III-III-5.html.

In 1919, Japan, as a member of the victorious Allies, gained official control of the Marshall, Gilbert, Caroline, and Marianas (except Guam) island chains of the Central Pacific. This came as part of a League of Nations Mandate. The development caused alarm among US planners, since the most direct route to the Philippines was now straddled by the nation most likely to threaten it. In 1914 Ellis was sent to Guam to assess its defenses, as the Navy was concerned about Japanese and German warships cruising the Marianas after the outbreak of World War I. Ellis responded with a detailed analysis of the island’s natural defenses and vulnerabilities as well as a plan for improving those defenses through fortifications and a mobile defense against amphibious landings.

It was on Guam that his advanced base work was first put to practical use. Guam was also where his tendency to work himself to exhaustion, resulting in depression which he treated with alcohol, first became a real problem. At one point Ellis was hospitalized for six days, where he was diagnosed with neurasthenia, which is defined by Merriam-Webster as “…a condition that is characterized especially by physical and mental exhaustion, usually with accompanying symptoms (such as headache and irritability), is of unknown cause but is often associated with depression or emotional stress, and is sometimes considered similar to, or identical with, chronic fatigue syndrome.” Ellis would be haunted by this condition, and the attendant alcoholism, the rest of his life.

The Washington Naval Conference of 1921-22 made the US strategic situation worse. The treaty ensuing from the conference laid out major restrictions on the five largest naval powers around the globe, including the US and Japan. Aside from warship tonnage ceilings, the treaty forbade the construction or improvement of bases outside the home waters of each nation. That meant the plans for Subic Bay and other defenses in the Philippines and Guam had to be scrapped. To be fair, the Japanese were also prohibited from building up the Mandates, but they were still astride the sea route to the Western Pacific and there was nothing to stop the positioning of blocking or delaying forces there.

John Archer Lejeune was no fool. He recognized that any campaign to relieve the Philippines and Guam would require someone to seize support bases for the fleet across the vast Pacific. He also saw an opportunity. There were rumblings that the Marines should be absorbed into the Army to save money. Ironically, the Corps’ hard-nosed performance in France was cited as a major reason for the proposed merger. Lejeune saw the need to conduct assault landings by a specialized force as the way to give the Marines a unique mission which would help guard their independence. The Navy also saw the advantages of such a force, giving Lejeune more insulation against the Army.

Ellis had written briefly about the advanced base role in naval strategy and, given his experience and relationship with Lejeune, was a natural choice to formulate a plan for the Marine Corps’ mission going forward. The task facing the Marines, as well as the Navy and Army, was daunting. The Gallipoli operation of 1915 supposedly proved that opposed amphibious ops were impossible. Conventional wisdom worldwide was that only limited landings at night were plausible in the face of determined resistance. Pete Ellis disagreed. Launching a successful amphibious operation under fire would be difficult, but it could be done.

Ellis engaged in a manic seven months of work, reportedly surrounded by dozens of maps, intelligence estimates, and geographic surveys. The result was Operation Plan 712, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia. This prescient study outlined the fundamental problems associated with assaulting island outposts in the Marshalls, Carolines, and Palaus as well as the basics of amphibious doctrine. Ellis stressed the importance of joint operations in support of task-oriented ground forces.

The landing was to be made at dawn or shortly thereafter, directly contradicting the European “lessons” from Gallipoli. The organization and deployment of the landing force was laid out in detail, from loading to reinforcement once it was ashore. Ellis discussed the importance of direct and indirect naval gunfire and air support for the landing force. Also included was a detailed discussion of the nature of the islands in question and the need for up to date intelligence on tides, weather patterns, reef formations, and the geography of the islands themselves. Estimates of enemy defensive tactics and weapons as well as projected enemy fleet actions in defense of the islands and attempts to retake them rounded out the discussion of tactics.

Ellis concluded that the Marine Corps was particularly suited for such operations and should prepare itself accordingly. He had no illusions as to the precise nature of the undertaking:

“To effect a landing under the sea and shore conditions obtaining and in the face of enemy resistance requires careful training and preparation, to say the least; and this along Marine Corps lines. It is not enough that the troops be skilled infantry men or artillery men of high morale. They must be skilled water men and jungle men who know it can be done. Marines with Marine training.”

Ellis’s plan was adopted in its entirety by Lejeune in mid-1921, forming the genesis of American amphibious doctrine as it would be practiced during the Second World War. Ellis had pointed the way to the US becoming the only nation which entered WWII with the capability to land an amphibious force under fire. But he seems to have become obsessed with proving the necessity for that capability. After the adoption of his work by Lejeune, Ellis convinced the Commandant to allow him to tour the Mandates, incognito, to scope out beaches, harbors, and any defenses the Japanese might be constructing.

Far East Tour

Lejeune arranged for Ellis to secure three months leave time, supposedly to travel in Europe for his health. He left Washington on 5 May, 1921. It was also arranged for the Office of Naval Intelligence to deposit funds for the trip directly into Ellis’s personal bank account, which he could access in person or by wire. Finally, Ellis gave Lejeune an undated letter of resignation, apparently to allow the Corps to avoid any public embarrassment if he were to be discovered and arrested by the Japanese.

Ellis originally traveled to Australia, supposedly as an agent for the Hughes Trading Company of New York, where he tried to book passage to the Mandates. On 26 October, he managed to get a travel visa from the Japanese consulate in Sydney, but there was no steamship service to the islands from Australia. Becoming frustrated at his lack of progress, Ellis determined to go to Japan itself, believing he could catch a ship from the port of Yokohama. He communicated with Washington, and his brother John, that he was taking ship for Japan and expected to proceed from there. He told John to watch the mail carefully and to file everything he sent because it would contain “information.”

Ellis’s communication with his brother was a symptom of how amateurish his self-imposed mission was. Ellis was no doubt confident of his own abilities, but apparently had no concept of operational security. He had briefly visited his family after he left Washington and had confided in his two brothers the nature of his trip. He did the same with his banker in San Francisco. In neither case was there any reason for him to do so.

Ellis had an attack of neurasthenia on the way to Japan and had to be admitted to a naval hospital when the ship called at Manila. It’s unclear how long he stayed in the hospital, but upon his release, he cabled Marine Corps HQ to inform them he was better and proceeding to Japan. He received a reply, signed by Assistant Commandant Neville, extending his leave by six months and authorizing him to continue. Since the response came from Neville, it’s generally assumed that Ellis’s entire chain of command knew about his “secret” mission.

Ellis stayed in Manila until July, 1922, when he felt strong enough to continue. Upon receiving permission from Neville, Ellis boarded ship for Yokohama, but not before cabling John Ellis, in the clear, “Proceeding Japan.” On his arrival, Ellis got the necessary visa and official approval for his trip to the Mandates, then decided to enjoy the nightlife.

Ellis could apparently raise hell with the best of them, since word of his activities quickly reached the US Embassy in Tokyo.

He reportedly hung out by the waterfront in dive bars and geisha houses, drunk most of the time. Even worse, word got back to the US Naval Attaché, Captain Lyman Cotten, that he was telling his new drinking buddies all about his mission to the Mandates. In early August, Ellis checked himself into the US Naval Hospital in Yokohama. He was released after a few days, but the doctor who treated him was summoned shortly afterward by the manager of the hotel where Ellis was staying. Ellis was very sick and delirious. He drunkenly informed the doctor about his now not-so-secret mission. On 1 September he was back in the hospital, once again diagnosed with neurasthenia. He stayed for a few days, but before he left he loudly announced that he was leaving for the islands on a Japanese steamer on the 14th.

He didn’t make the ship and showed up at the hospital again on the 22nd, receiving treatment for alcoholism. At this point, Cotten had had enough. He gave Ellis the choice of voluntarily going home or being ordered home on a military transport. It’s unclear what answer Ellis gave Cotten, but what is known is that he cabled his bank in San Franciso for a thousand bucks, packed his bags, and walked out of the hospital on the night of 6 October, 1922. He took a train to Kobe and hopped a ship for Saipan the next day. Ellis spent three weeks on Saipan, travelling the island making detailed maps and charts of the island’s geography and tracking down the route of a proposed railroad line.

There weren’t any defenses for him to see but there’s little doubt he was mentally planning the assault of the island which wouldn’t take place for another twenty-two years. He quickly drew the attention of the Japanese authorities and checked out of his hotel to avoid them. A contact arranged for him to stay with a native family, but since he made no attempt to hide his activities, the cops picked up his trail again and tailed him everywhere. Surprisingly, they allowed Ellis to leave the island with all his notes on 3 December.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Saipan, Kusiae, and the Beginning of the End

Ellis spent the next seven months in the Marshalls, Carolines, and Palaus, repeating his exploits on Saipan. He made contacts with European traders, who often gave him a place to stay, but was under constant surveillance by the Japanese and native police who usually didn’t even try to hide their interest. Ellis brazenly plowed on, though his drinking problems had returned with a vengeance. He often complained about the attention from the cops, but kept on doing his thing.

On Jaluit, in the Marshalls, he was befriended by an American missionary named Mother Jesse Hoppin. Ellis first came to her attention when the captain of the ship on which he was traveling sought her help after Ellis became very ill during the two-day passage from the island of Kusiae. Ellis had been given several bottles of whiskey by a German trader who had helped him there, after being told by the American about his special mission. Once on the ship, he locked himself in his cabin and drank them all.

Mother Hoppin visited Ellis in the local hospital and, upon his release, housed him at her mission, where she constantly talked to him about his “wicked habit.” Ellis attended services with her and seems to have stopped drinking while he stayed with her. Still posing as a commercial agent, though he didn’t seem to do any actual trading, Ellis began hopping an inter-island schooner, supposedly to visit coconut plantations. It didn’t take long for word about his extensive sketching and note-taking, as opposed to trading, to get back to the local police chief, who started taking the schooner whenever Ellis did.

As before. Ellis was annoyed by the attention, but made no real effort to hide what he was doing. Mother Hoppin eventually served as Ellis’s confidante as he used Jaluit as a base while in the Marshalls. He told her about his mission (because of course he did), and began giving her his notes and sketches. Ellis also gave her his copy of Naval Code F2, which he had pasted inside the back cover of a trading publication and used for his infrequent communications with naval intelligence, . He was aware of the interest of the police and asked her to send his work to his brother, John, in case something happened to him.

The Japanese authorities, not wanting to cause an incident, tried to stop Ellis by denying travel visas or telling him no berths were available on the schooner. Mother Hoppin had assigned several native boys to escort and watch him in his travels, so Ellis used them to secure sleeping room on deck, which he would take himself. On one trip, between Kwajalein and Jaluit, it was standing room only on deck, thanks to a shipment of copra, so Ellis and his escort stood up the whole way.

Early in 1923, Ellis’s alcoholism returned with a vengeance. Mother Hoppin had removed all the liquor from his quarters while he was away and forbidden local merchants to sell it to him. Ellis just used his young escorts, who also served as houseboys, to buy it for him. They smuggled it in to him in food containers. Ellis drank whiskey from a teacup during his meals and chased it with beer. Afterward, he would drink a mixture of water, lemon juice, and Epsom salts to make himself vomit it back up. He became increasingly erratic, and the local police chief entered his quarters one day when he was passed out and looked at his growing intelligence cache. Ellis exploded when he learned of the intrusion, throwing his pistols at his houseboy in a fit of rage.

Ellis left Jaluit in March, 1923, heading for the western Carolines and the Palaus. He left much of his work with Mother Hoppin, By this time, the Japanese were wise to what he was actually up to and prevented him from doing anything but visiting the homes of local traders. His attempt to visit the island of Truk came to nothing, as the Japanese refused allow foreigners to disembark. In April, Ellis arrived at the island of Koror in the Palaus, where a trader named William Gibbons arranged a house and a native “wife” for him.

Ellis tried to continue his survey mission, but he was closely followed by the native police, who hampered him at every turn. He began drinking even more, reportedly tearing down a wall in Gibbons’ house because he thought his host was hiding whiskey from him. He continued to employee native boys buy whiskey and beer for him. A local doctor tried to convince him to enter the hospital, but Ellis refused. According to his native wife, Ellis ate very little but consumed over three hundred bottles of beer a week.

Seeing Ellis’s weakness, the Japanese authorities arranged for alcohol to be delivered to him, knowing he would drink himself into a stupor. On 12 May, 1923, two bottles of whiskey were brought to Ellis’s house. He promptly drank them, soon becoming delirious. At one point, he cried out that he was “…an American spy sent by higher authorities from New York.” He also called for his parents. He died later that day.

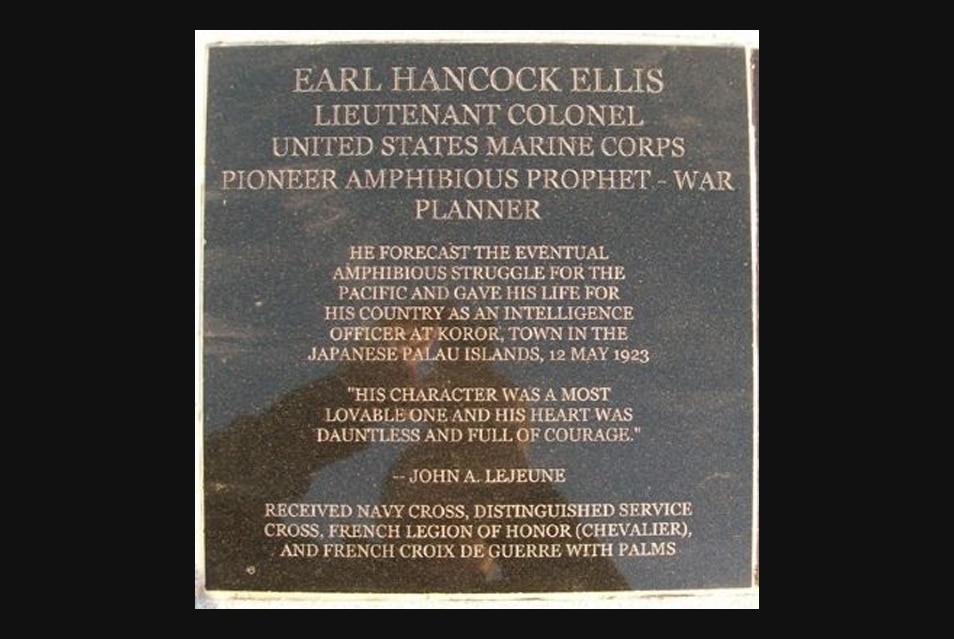

Ellis Marker, Pratt, Kansas. Photo Credit: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=65085.

Conspiracy Theories

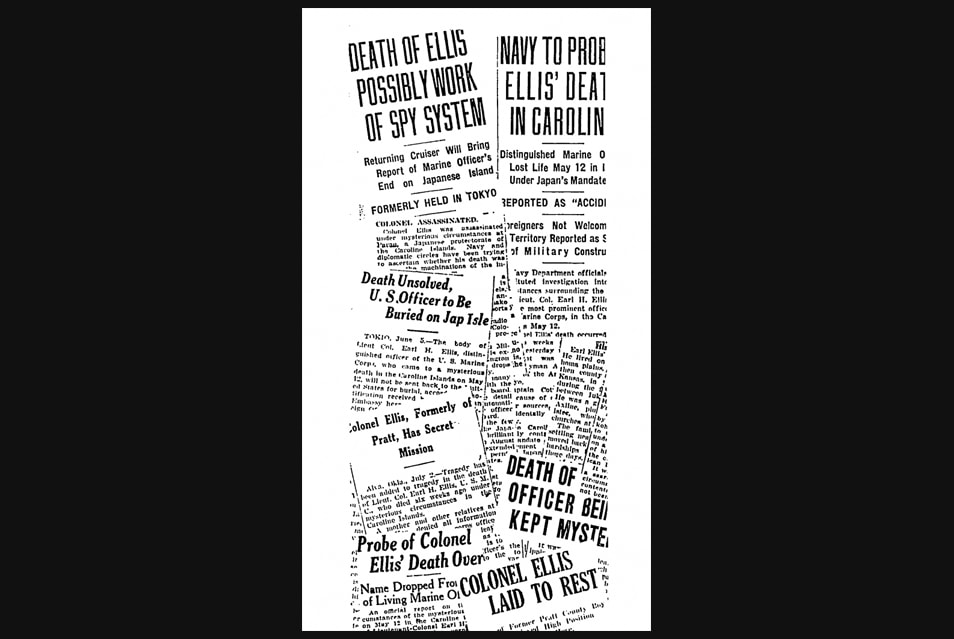

Ellis was buried in a Japanese cemetery. The Japanese authorities notified Captain Cotten in Yokohama, who dispatched Chief Pharmacist’s Lawrence Zembsch to recover Ellis’s remains. The story goes that Cotten saw a chance to gather intelligence in the islands and that Zembsch’s mission had a clandestine aspect to it. Rumors also surfaced that Ellis had been deliberately poisoned by the Japanese. The fact that Ellis’s remains were cremated before being returned to Yokohama fueled that particular rumor.

It got worse when, upon arriving back in Yokohama, Zembsch was found gravely ill and nearly catatonic in his cabin on the Japanese steamer on which he was travelling. Zembsch was immediately hospitalized, but before he could recover and give his report, was killed in the great earthquake of 1 September, 1923. That earthquake leveled much of Yokohama, including the naval hospital. US newspapers erupted with the story that an American officer had been murdered by the Japanese, who then poisoned another American (Zembsch), who had been investigating the incident.

The story eventually died out due to lack of evidence, though official investigations continued into the 1960s. The conspiracy theory has never gone away entirely, though it does seem that the Japanese were merely trying to keep Ellis from spying on them, as opposed to killing him.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Ellis’s notes and sketches were never recovered. Mother Hoppin turned over what she had to the Japanese upon learning of Ellis’s death. It can only be assumed that anything else he had was confiscated. His copy of the F2 Naval Code was returned to the Office of Naval Intelligence in 1924 by a Japanese naval officer, who said “Here is something we know you wouldn’t want to fall into the wrong hands.” He then turned and left. Inside the package he left was the book with the code pasted in the back, no doubt compromised.

The Ellis Legacy

Pete Ellis was a Marine’s Marine. When I first started researching him a couple of years ago, I saw the same stuff that everyone interested in amphibious warfare sees: he predicted the war with Japan and how it would be fought. True enough. He even predicted that two regiments would be needed to take Eniwetok Atoll. He was correct, as the 22nd Marines and the 106th Infantry Regiment did just that. It even went pretty much the way he said it would.

After that, everything became about his sensational mission to the Japanese Mandates. Sensational it was, but it was also an unmitigated failure that could very well have blown up into a major international incident. As it turned out, the Japanese didn’t want the attention, especially since they knew no real damage had been done. As it also turned out, they hadn’t been building any defenses and wouldn’t until the 1930s. Still, Ellis’s notes would have been invaluable intelligence assets once the Central Pacific Campaign of 1943-44 kicked into high gear.

What was missing from Ellis’s story, which became evident once I started reading what he wrote, was the long-term impact his work had on how the US Marines and Army would approach the problem of assaulting heavily-defended island fortresses. The real work in that area would not get done until the mid-1930s and early 1940s, but thanks to Ellis, they had a solid doctrinal framework to build on.

Unidentified US Marine off Eniwetok. Photo Credit: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/202591683208943856/.

Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia is the foundation on which American amphibious warfare is built. It led directly to the groundbreaking Tentative Manual for Landing Operations, published by the Marine Corps in 1934, which in turn led to the Navy’s FTP-167 (Landing Operations Doctrine), which US forces took into WWII and used to bludgeon the Japanese into submission as the US amphibious steamroller got cranked up by early 1944.

Any doubt that the Marine Corps recognizes Ellis’s importance can be put to rest by a visit to Marine Corps University at Quantico. Ellis Hall, which houses a bust of Pete as well as a large venue where amphibious doctrine is taught, is named for him. The library also features a display case with some of his effects. On a personal note, while visiting the Marine Corps archive at Quantico last year, I heard Ellis’s name mentioned over and over by Marine officers conducting research for their own projects. I was fortunate enough to get my mitts on a digital copy of the original typewritten manuscript of Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia as well as Lejeune’s order adopting its contents in full as official war plans.

Ellis Hall, Quantico Marine Base – Author’s photo

Finale

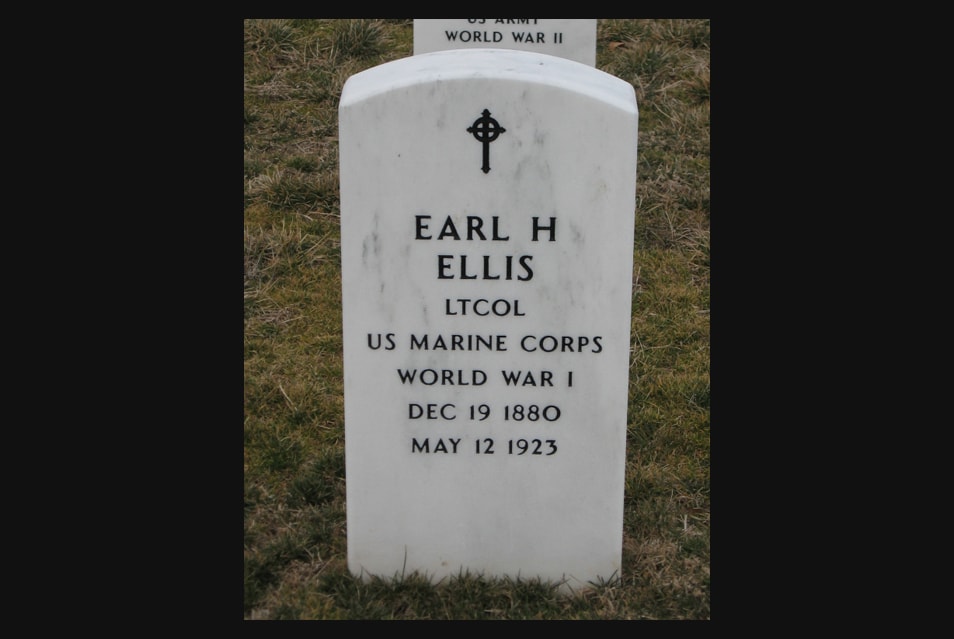

For his part, Lejeune burned Ellis’s letter of resignation, and Pete’s ashes were buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. Ellis’s brilliance is beginning to be recognized outside the Marine Corps, in terms of his ability to read the political and strategic realities of his time and translate that vision into real operational capabilities. An excellent introduction to Ellis was recently published to that effect, which reproduces much of his work, word for word, in an effort to spark thought and discussion along those lines in today’s rapidly-changing strategic environment.

Ellis Gravestone, Arlington. Photo Credit: http://hickeysite.blogspot.com/2011/07/lt-col-earl-hancock-ellis-1880-1923.html.

No doubt, Pete Ellis was ballsy, and reckless. But he was also a shrewd strategic and operational visionary. The plaque at Quantico which commemorates Ellis reads

“His heart was dauntless and full of courage.”

I wonder if a guy like him could rise to prominence today, given his issues and the political climate? How many Pete Ellises are we missing out on?

-Bucky Lawson

Follow EOTech on Instagram, @eotech.

[arrow_feed id=’47175′]

Read Up:

– Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia by Earl H. Ellis http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/ref/AdvBaseOps/index.html

-21st Century Ellis – Operational Art and Strategic Prophecy for the Modern Era edited by B.A. Friedman

-Pete Ellis – An Amphibious Warfare Prophet by Dirk A. Ballendorf and Merrill L. Bartlett

-Assault from the Sea – Essays on the History of Amphibious Warfare edited by Merrill L. Bartlett

-“Assault from the Sea,” by Allan R. Millett, in Military Innovation in the Interwar Period edited by Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett

-The US Marines and Amphibious War by Jeter A. Isely and Philip A. Crowl

-War Plan ORANGE- The US Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945 by Edward S. Miller

Mad Duo, Breach-Bang& CLEAR!

Comms Plan

Primary: Subscribe to the Breach-Bang-Clear newsletter here; you can also support us on Patreon and find us on Pinterest.

Alternate: Join us on Facebook here or check us out on Instagram here.

Contingency: Exercise your inner perv with us on Tumblr here, follow us on Twitter here or connect on Google + here.

Emergency: Activate firefly, deploy green (or brown) star cluster, get your wank sock out of your ruck and stand by ’til we come get you.

About the Author: William “Bucky” Lawson has had a thing for military history since the sixth grade when he picked up a book about WorldWar I fighter aces. Since then he has studied

[Grunts: bibliognost; oh, and polrumption…oh hell, and incabination too.

I didn’t know one could be diagnosed with neurasthenia. I thought neurasthenia was an obsolete historical term from a century ago.

Perhaps a better source of current medical information would be the CDC website.

You say that Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is “often associated with depression or emotional stress…and the attendant alcoholism”. This would likely be considered offensive to many CFS sufferers. Just as it would be offensive to say this about those suffering from Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s, cancer, muscular dystrophy or any other chronic disabling disease.

What? Try again when you’re off the bottle.

I used the diagnosis that was current at the time. Ellis was diagnosed a century ago. Offensive or not, those were the symptoms, and they are central to trying to understand his erratic behavior.